Lifestyle

Anti-apartheid detainee delves into dark past in new memoir

In 1969, at the age of 21, John Schlapobersky was arrested for opposing apartheid, primarily through poetry. He was tortured, detained, and eventually deported. Interrogated through sleep deprivation, he later wrote a diary secretly in solitary confinement.

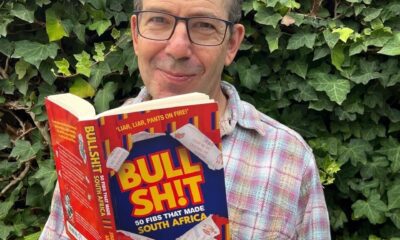

Titled When they came for me: The Hidden Diary of an Apartheid Prisoner, his newly released book, based on his diary written on toilet paper and hidden inside a pen while in prison, tells this little-known story of survival and defiance.

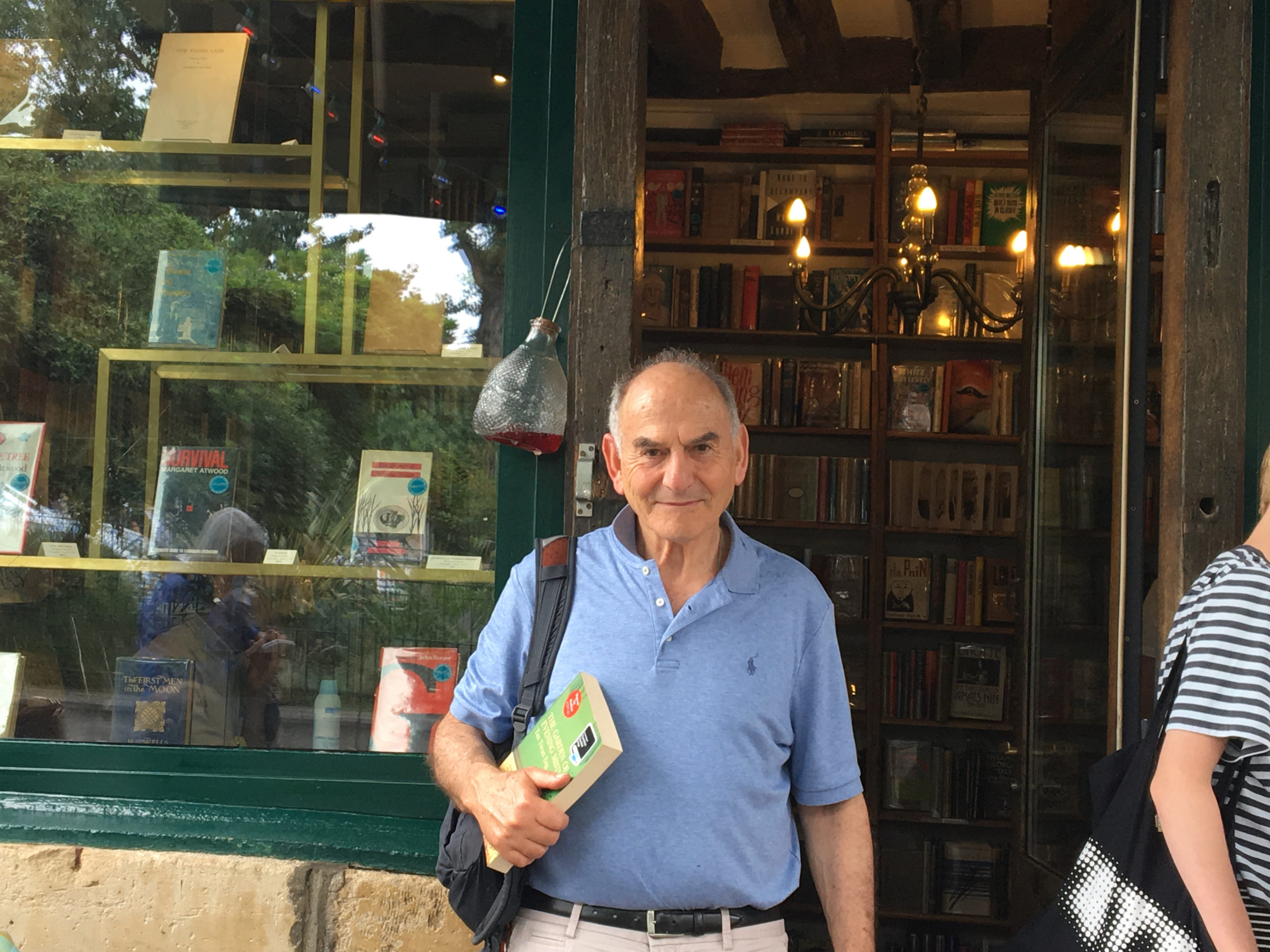

After being forcefully deported, his return to South Africa for Cape Town’s Jewish Literary Festival on 21 March allows him to come full circle and share his riveting, devastating, and hopeful history.

“I was supposed to be a man by the time I turned 21, by anyone’s reckoning. By the apartheid regime’s reckoning, I was also old enough to be tortured,” he writes in his introduction. “Looking back, I can recognise the boy I was. The eldest of my grandchildren is now approaching this age, and I would never want to see her or the others – or indeed anyone else – having to face any such ordeal. At the time, my home was in Johannesburg, only about 30 miles (48km) from Pretoria, where I was thrown into a world that few would believe existed, populated by creatures from the darkest places, creatures of the night, some in uniform. I was there for 55 days, and never went home again.”

He experienced a week of sleep deprivation, most of it standing on a brick under a bright light, and six weeks in a cell near the gallows in prison “listening to the condemned sing through the nights before execution, and then in the terms and nature of deportation. In spite of having written a book about it now, as I put it all down 54 years later, it’s still an extraordinary ordeal.

“While in detention, my survival was shaped by the belief that I could protect my life by describing what was happening,” he says. “I stole a pen from the interrogators’ desk and took it with me into solitary confinement. There I kept a daily chronicle on toilet paper, kept a calendar on the flyleaf of the Bible that I was allowed, recorded lines of biblical text and poetry of my own, and kept further coded notes on what had happened during the interrogation.”

So how did a peaceful poet come to be arrested, detained, tortured, and deported by the apartheid police? “I had no apprehension of what was to come prior to my arrest,” he says. “Although born in Johannesburg, I had grown up Swaziland and was studying in South Africa on a British passport. A number of my relatives held positions of distinction in Johannesburg’s life – in law, commerce, and local government – and I had no idea I could be in any political risk, given the limits to my opposition, which was confined to student politics and interracial writers’ workshops.

“But in the winter of 1969, a wave of arrests under the Terrorist Act took place throughout the country, and I encouraged several of my black friends to go and stay with my family in Swaziland to get out of harm’s way. They didn’t do so in time, and were detained. My own arrest followed – an appalling shock. Police authorities released me on condition of deportation 55 days later. I was one of only two white people arrested at the time, and was taken from my cell in Pretoria local prison, given half an hour to say goodbye to my family, and put on a plane to Israel. I didn’t appreciate that this was to be the end of my life in South Africa. A free return was impossible until after the Mandela government came to power 25 years later.”

The ripple effects of these events had a profound impact on Schlapobersky’s life and that of his family. “My parents’ marriage broke down in the aftermath of my detention. It was one of the casualties of those terrible times.” He settled in London, where his siblings came to live with him and his girlfriend, whom he later married. “So I was not only a displaced refugee, but was also in loco parentis to two teenage children.”

The one positive outcome of the experience is that it led him to become a leading psychotherapist and author. He is a training analyst at the Institute of Group Analysis, and was a founding trustee of Freedom from Torture in 1985. His publications include From The Couch To The Circle: Group-Analytic Psychotherapy In Practice (Routledge, 2016), which won the American Group Psychotherapy Association’s Alonso Award in 2017 and is in translation to other language editions.

He could have become a different kind of writer. He was close friends with South Africa’s poet laureate, Mongane Wally Serote, long before his name came to the attention of the public, and their earliest poems were drafted together. “But my arrest and deportation cost me my own developing voice as a poet. I still write poetry when deeply moved, but have published little,” he says.

Why write a book now? “Over the years, I’ve been approached by many journalists and some of them have done a reasonable job with their versions of my experience. But I’ve always wanted to tell my own story, on my own terms, and in my own way,” he says.

It was a visit to the NASA Space Centre and the Apollo Museum that really prompted him to write a book. “Neil Armstrong and his crew walked on the moon on the 39th day of my detention, which a prison warder told me about in passing. That night, I tried and failed to view the moon from my cell and feared I might never see it again.

“When I saw the little speaker in Houston through which Armstrong’s voice was broadcast to the world – ‘One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind’ – a world that didn’t include me, I was overwhelmed by my own history and came home resolved to write it down, once and for all,” he says. “It took about two years, and I remain deeply grateful to the two publishers who produced the book – Berghahn Books for the international edition, and Jonathan Ball Publishers for the South African one.”

Recalling the experience brought up feelings of sorrow, horror, and disbelief. “Reliving it is like eating nails,” he says. “I could get to grips with it only for limited periods of time, and would then find I had to return to the present to recover. When immersed in this narrative, holding the old Bible, or looking at the toilet paper diary, the material had a strange quality that corroded my well-being. I found I could get distracted and moody and become careless about people, arrangements, and possessions. Now that this task is done, I look forward to being on better terms with my past, without so much threat from its shadows.”

Schlapobersky is a practicing and observant Jew. “I belong to a wonderful Masorti (Conservative) community here in London,” he says. “I regard Israel as my spiritual home. It’s also the country that helped to save my life. South Africa is still my home, so coming to the Jewish Literary Festival in the port that my grandparents came to at the beginning of the 20th century brings together just so much. I’m grateful and delighted.”

- John Schlapobersky will be a special guest at the Jewish Literary Festival 2023 in Cape Town on 21 March. He will be addressing “The personal in the political”. To book or find out more about the festival and special hotel offers, go to www.jewishliteraryfestival.co.za or call Beryl on 082 490 6652.