Tributes

KZN’s last Holocaust survivor leaves legacy of love and inspiration

The last remaining Holocaust survivor in KwaZulu-Natal, anti-apartheid activist Carmela Heilbron, passed away in the early hours of 13 January in Durban.

Heilbron, her mother and sister were the only Holocaust survivors in their immediate family. Her grandparents, father, and two brothers were murdered.

After World War II, Heilbron settled in South Africa, where she became politically active in the anti-apartheid movement and was jailed several times for her activism. She was also professionally involved in early childhood education outreach projects.

Steven, her son, speaking at her funeral on 15 January, said, “She could love like nobody could love. She will always be in our hearts, and her hugs will last much longer than from the moment that she let go.

“Take a good look at what’s happening around you. Don’t ever turn around and say it’s not there because it’s not affecting you,” Heilbron once said, according to a testimony from the Durban Holocaust & Genocide Centre (DHGC), prepared for a publication in Survivor Stories volume one.

Heilbron (née Haymann) couldn’t be sure of her exact birthdate. It could have been anywhere from 1938 to 1940. She was probably born in Lithuania. Her first clear memories began around the age of seven. “I didn’t remember. I elected not to remember. This is the story as it was told to me.”

As a child, Heilbron grew up in the Kovno ghetto, established by Nazi Germany to hold the Lithuanian Jews of Kaunas during the Holocaust. At its peak, the ghetto held 29 000 people, most of whom were later sent to concentration and extermination camps or were shot at the Ninth Fort stronghold in Kaunas.

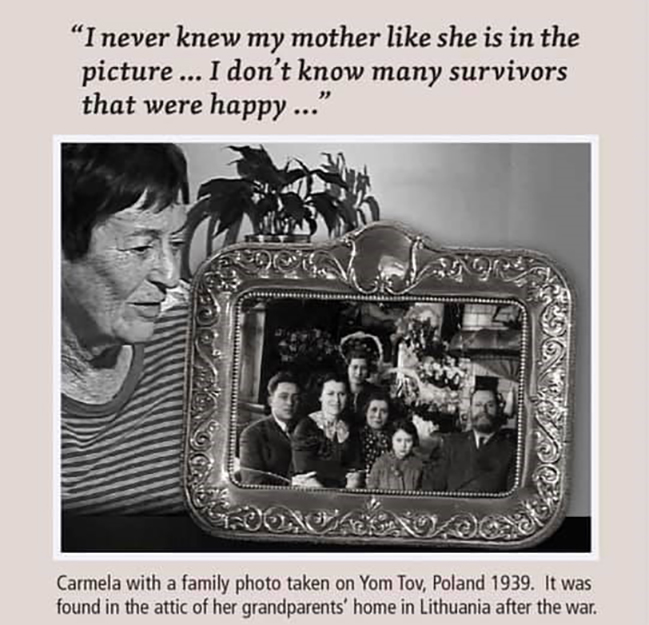

Heilbron remembered very little except sleeping with her sister and grandmother like sardines on the floor. She knew her mother was with them at that time, but couldn’t recall her face.

Dr Elchanan Elkes, the head of the Ältestenrat (council of elders) in the Kovno ghetto, helped to create a scheme to smuggle out young children from the ghetto with the help of the Catholic Church. Heilbron’s mother managed to smuggle her daughter out of the ghetto in this way.

“The smallest children [got] an injection. Then they arranged to drop these children into a sack and into a cart as if it was waste,” Heilbron recalled. “I was the first child put over the wall [in this way] and taken to a Catholic safe house.”

Heilbron spent the following years protected by a group of Catholic nuns and priests. They were constantly on the move to avoid detection by the Nazis. She remembered once being hidden inside a pit toilet during a Nazi raid of the convent. As a result, she was left with “a whole lot of fanatical hang-ups” about being clean. For example, for years she was unable to use a public toilet without wearing a mask. “Growing up, I had some very strange habits,” she said.

The nuns handed Heilbron over to the Red Cross at the end of the war. She was adopted by her father’s friend and colleague, Dr Max Levin. Eventually, her mother, who had survived the Auschwitz concentration camp, regained her strength, and began searching for her child. However, when she finally located Heilbron, Levin wouldn’t give her up. Heilbron’s mother arranged with a Jewish underground group to kidnap her from the Levin family.

“Although I hadn’t seen her probably since I was two, I just knew it was my mother and I was related to her.”

Once Heilbron was reunited with her mother and sister, they made their way to Tanzania to start a new life as the only survivors of their immediate family. “Nobody talks about [my grandparents, father, and two brothers who were murdered in the Holocaust]. My aunt told me about them, but my sister refuses to talk about them,” she said.

Heilbron said she felt she never really knew her mother. Once living in the safety of Tanzania, she believed her mother returned mentally to Auschwitz. She lived with dementia for seven years until her death. She thought her daughter was a kapo, an inmate of a Nazi camp appointed as a guard. “If I walked into the room, she would get up and huddle under the bed,” Heilbron said.

Heilbron eventually settled in Durban, where she met and married her husband, Lew. The couple had two children, Steven and Mandy. Although she opened up to members of the local community about her story, she gave her testimony on camera only in 2008 because “I didn’t regard myself as a survivor,” she said.

Through a connection in the Durban community, she was reunited with the other girls the nuns had protected. They had been searching for her for 40 years, and Heilbron met them in London. “They knew more about me than I knew about myself.” This group of survivors succeeded in having the priest and the nuns who had rescued them recognised at Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

In 2008, Heilbron became a guide at the emerging DHGC. She went on to become a stalwart volunteer at the centre, working there until 2014. She was central to the team and integral in all the centre’s programmes. She made a profound impact on visitors, particularly high school students, when sharing her testimony.

“Today I learnt a lot of things, but what moved me the most was a survivor story of Carmela Heilbron and how courageous she was,” said one of the hundreds of students who had the privilege of spending time with Heilbron. “After trauma, she dedicated her life to helping others.”

Heilbron constantly reminded visitors to the centre what her mother had told her. “No matter what people take from you, they cannot take away your education.”

“The important message is to take action. Speak up, because when you don’t speak up, it just compounds itself into a hideous situation,” Heilbron said.

Heilbron suffered another tragedy when her daughter, Mandy, passed away at the age of 36.

Speaking at his mother’s funeral, Steven said, “When I reflect on my mom, I think of three things. She used to say to me, ‘Climb the mountain to see the world, but not so the world can see you.’ That was reflective of her selflessness. My mom was incredibly dedicated to her children, husband, faith, the Jewish people, and Jewish identity.

“The other thing she used to tell me is, ‘There’s no great gain without great sacrifice.’ This is something I’ve probably taken too seriously in my own life, but it was a guiding light for us as kids. Lastly, she used to say, ‘You live and die through your Jewish identity.’”