Featured Item

Famous friendship between Sobukwe and Pogrund goes on screen

Published

7 months agoon

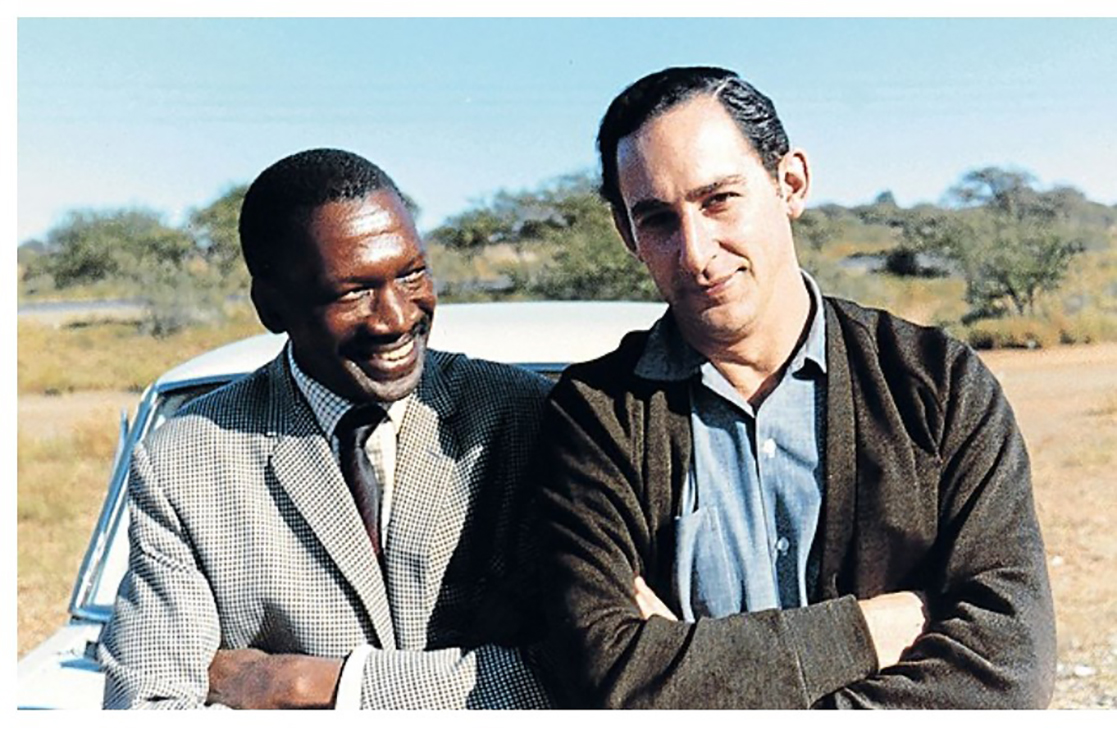

Veteran South African journalist Benjamin Pogrund, who now lives in Israel, initially never wanted his own life story to be part of the narrative of the upcoming series based on his biography of struggle activist Robert Sobukwe titled How Can Man Die Better.

“However, the filmmakers, who are from America, explained that the friendship between Bob [his nickname for Sobukwe] and I was so extraordinary, especially at that time, that they felt it needed to be included,” says Pogrund, speaking to the SA Jewish Report from Jerusalem. “They also felt that highlighting this friendship between a white Jew and a black Pan-Africanist would go a long way towards combating the antisemitism and racism that is rife in America today.”

Developed by Inyani Corporation, a global filmed entertainment production company, and its filmed entertainment production subsidiaries in South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany, “The subject of this political thriller drama series is unique,” says supervising producer Pulane Shomang. “The project, which has the working title of An Extraordinary Friendship, has all the elements required for suspenseful, thrilling entertainment.”

Michael Fisher, the chief executive of Inyani Corporation, describes the story as “a gripping tale of courage, friendship, and resistance, which brings to life the true story of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, an immensely popular South African black Pan-Africanist leader, and Benjamin Pogrund, a Jewish South African journalist. Set against the backdrop of apartheid-era South Africa, this captivating historical political thriller follows the two men as they embark on a relentless 20-year battle against the violently racist white apartheid minority regime.”

The film “delves deep into the lives of Sobukwe and Pogrund,” says Fisher. “As Sobukwe emerges as a symbol of hope, the apartheid government sees his unwavering determination and influence as a threat. Unjustly imprisoned for incitement for organising a civil disobedience campaign in 1960 and subjected to the infamous ‘Sobukwe clause’, which allows the apartheid regime to keep him detained after the completion of his prison sentence, Sobukwe endures the harsh conditions of solitary confinement on Robben Island.” Meanwhile, “Pogrund, an anti-authoritarian journalist, rises through the ranks, determined to report on the injustices inflicted on Africans.”

Pogrund has become deeply involved in the project over the past two years, which he says has been a fascinating, meaningful, and enjoyable experience. However, it’s still very much a work in progress, and Pogrund is unsure at what point in his and Sobukwe’s life stories it will end its narrative.

He reflects on being introduced to Sobukwe by chance, when, “In 1957, I was greatly interested in black politics. The African National Congress [ANC] was in turmoil. It was one of those instant friendships. We disagreed a lot but also had a lot in common. I discovered I had a natural empathy for his thinking. I later discovered auto-emancipation: the idea that if you respect yourself, the world respects you. There was a lot in common between Zionism and African nationalism.”

Over the years, their friendship grew into what Pogrund describes as being as close as brothers. Pogrund emphasises that Sobukwe was the apartheid regime’s “most feared” prisoner, which was clear from the way they treated him, isolating him from other prisoners on Robben Island, essentially placing him in solitary confinement for six years in an isolated hut.

“They effectively threw away the key,” says Pogrund. “Apartheid was evil, but the craziest things happened,” one example being was that only he was allowed to visit Sobukwe. Pogrund was doing his PhD, and he applied to visit Sobukwe as part of his research, which was granted.

“They didn’t allow it for research, they allowed it because they wanted to hear what he was thinking,” says Pogrund. The pair knew they were being listened to, yet Sobukwe looked Pogrund in the eye, and said something along the lines of, “If they release me, I will go back to my activism.” “He doomed himself. It was the most courageous act,” Pogrund says.

The friends were also allowed to write to one another, which they did very carefully, hoping to avoid being censored. “We discussed many things – even Israel and Judaism,” says Pogrund. “He even reflected that he would have liked to be Jewish.”

After Sobukwe was released but put under house arrest in Kimberley, Pogrund and his family continued to be his main source of support. It was Pogrund who ensured that Sobukwe saw the best doctors as his health began to fail, but by then it was too late. Sobukwe died at the age of 53.

Co-producer and Sobukwe’s grandchild, Mangaliso Tsepo Sobukwe, says, “Since my youth, I have dreamt of being part of a project that acknowledges the extraordinary relationship between my grandfather and Benjamin Pogrund and its impact, not only on the course of the lives of the two friends, but on those around them. I’m humbled and honoured, as a member of this distinguished team, to continue the mission which my late father, Dinilesizwe Sobukwe, began and tasked me to continue: to tell the story.”

Pogrund says Sobukwe has mostly been forgotten by history for two reasons: first, he died young, and second, the ANC was the “victor” as the leader of the struggle after Sobukwe split to form the Pan-African Congress, “and it’s the victors who write history”. He hopes the film will return Sobukwe to his rightful place in history and be an enduring inspiration.

He says his book on Sobukwe continues to be re-printed. “The growing interest in him flows from the terrible state that South Africa is in. He’s a shining example of what could have been. He had integrity, honesty, and a total commitment to the people. He would never have allowed the corruption that has taken place.”

Along the same lines, Pogrund says that his recent article on the situation in Israel in which he stated that Israel was, in fact, heading towards being an apartheid state, was “pulled out of me” after many hours of reading, debating, and thinking. He has been deeply concerned since Israel passed its nation state law in 2018. “I’ve become more fearful in recent months, and felt I had to say something.” He emphasises the article was initially written for an Israeli audience.

He knows it has caused distress, particularly in the South African Jewish community, and says, “I didn’t want to write it, but I knew I had something only I can say, and I needed to say it. The reality is I’m just a messenger. Jewish morality is at stake.”

He’s aware that the enemies of Israel and the Jewish people have twisted his piece for their own gains, but he says such “lies” and “cynicism” aren’t new from that camp. What’s more important is that the Jewish community wrestles with Israel’s current reality, and doesn’t shy away from such discussions because of how they may be twisted.

Returning to the film, Fisher says, “It’s an incredible honour that Benjamin has entrusted us to tell this story. In the face of contemporary struggles, this historical narrative becomes even more impactful, inspiring audiences to seek common ground and solidarity in the pursuit of a more just and compassionate world.”

yitzchak

Sep 22, 2023 at 1:34 pm

an APLA a day keeps Dr ANC away