Featured Item

Farm Killings shines spotlight on SA’s culture of violence

Published

2 years agoon

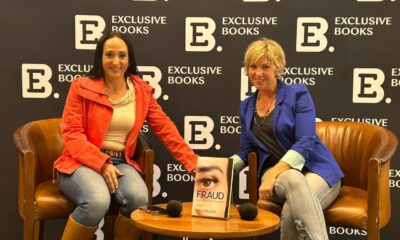

Farm killings make up only half a percent of all homicides reported each year in South Africa, but they say a lot about society and go to the heart of the problems in the country. That’s why they dominate the national narrative on violence, says Dr Nechama Brodie.

Brodie challenges many of the myths used to narrate farm killings in her new book Farm Killings in South Africa. This compelling and heart-rending book includes almost a century of news reports, legal cases, and expert research to try and gain insight into South Africa’s legacy of violence on agricultural land.

“Researching this book has been without question the most unpleasant and distressing content I’ve ever read on mass,” Brodie wrote in Farm Killings, her second book about death.

She said she nevertheless took a macabre interest in writing the book because of her deep-seated desire to set right the things that are wrong.

“I think this is a goal journalists share,” she said during a discussion about her book at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre on 13 October. “A lot of the time we cover social injustice or wrongs because we hope through coverage to enable improvement. Crime is a massive problem for South Africa because it derails every aspect of our lives. It undermines our confidence in each other and the country. So, several years ago, I started researching crime to try and understand it better in the hope that research would enable us to develop better strategies.”

She said her research consisted of the most violent content she had ever encountered because the coverage was very detailed. “Even femicide stories don’t get that level of coverage.”

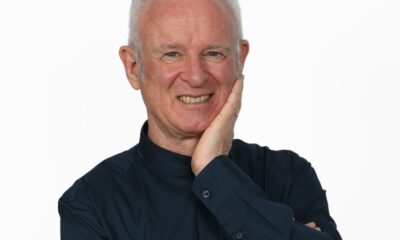

Professor Anton Harber, who asked Brodie some questions at the discussion, said, “I was struck that it’s a book by somebody who is both a journalist and researcher academic. It has the characteristics you expect from both. Very readable with some remarkably interesting, new, and valuable research. It’s an important book because it goes to the heart of some important South African issues.”

Brodie didn’t interview people affected by farm killings. “That would be a journalistic instinct – to find people to tell the story to humanise it. Why did you take this approach?” Harber asked.

Brodie responded, “A number of reasons. First of all, dealing with death on paper is much easier than dealing with the fallout, the emotional toll on the people whose families have been completely devastated through acts of violence. It’s really about choosing a kind of methodological approach that removes me. I’m doing it for my own protection. Dealing with death at the volumes that I do, violent death in the thousands, it becomes overwhelming.”

She said her ability to be objective may have been affected if she had to choose which people to interview, and hear them relive their trauma.

“One of the things that struck me is Afrikaans media articles about farm killings. They have tended to cover it much more extensively. The same journalist’s names appeared over and over again. They covered one event after another from month to month. I could imagine very much as a journalist what it must have been like to be sent out to another farm on another weekend to go interview a family who had just lost one, two, or three family members in one act. I was trying to imagine the absolute terror or trauma those journalists felt at once again having to go into that hole.”

Brodie said her research shows that farm murders are rarely committed for political reasons, but the management and discussion of how they are investigated is usually heavily politicised.

She wrote about farm killings instead of doing another book about a much larger category of murders in the country, because of the events that transpired in Senekal following the murder of 21-year-old Free State farm manager Brendin Horner in 2020.

“At the time, we had white farmers gathering, protesting, running into the jailhouse and the court building, singing Die Stem. On the outside, you had Economic Freedom Fighters [EFF] supporters come into town, chanting ‘Kill the Boer’. I realised how invested politicians are in this narrative. They do nothing to solve it because it’s suitable for them. For politicians, polarisation is much more likely to drive people to the polls and to make people vote for them. Unity and community are much less likely to make somebody vote for the African National Congress, EFF, or Democratic Alliance. None of these parties are invested in the solution. They are all invested in maintaining this problem because it’s useful for them. It produces massive media coverage and massive hype.”

Brodie wrote about farm killings instead of farm murders in the book, so she’s not looking for a legal finding of murder.

“I’m looking at deaths of farmers, farm workers, and other people. One of the big questions is what is a farm? The government over the past several years has tried to broaden the definition of farm killings, but there’s no murder category called “farm killings”. The government has now broadened the definition of farms from agricultural areas to the rural areas.”

Brodie’s book tries to categorise these kinds of things. It also draws attention to South Africa’s poor counts of farm killings. “In the 1980s, only about half of black deaths in South Africa were documented. There’s a huge amount of information we don’t have. We have no way of recouping it, so I use journalism sources as a way of kind of connecting little bits. We don’t know where we’re counting them because there’s no concept of what a farm is.”

Brodie found South Africa’s situation troubling when she researched violence in the country. “I don’t have an answer to why we are so terrible to each other. There are other countries that have very similar historical profiles of terrible violence which aren’t in the same state of violence we are now, but there’s something specific about South Africa that has dehumanised us and allowed us to dehumanise others.”