News

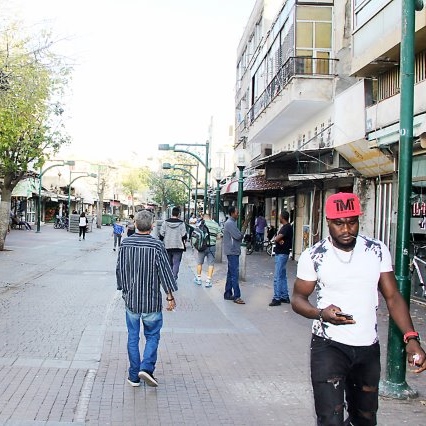

In Tel Aviv’s African neighbourhood, asylum seekers strive for normal life

Published

6 years agoon

By

adminBEN SALES

Pizza, his speciality, will go into the oven in the evening, Al-Aldoum assures me repeatedly. He makes a regular crust with tomato sauce, then covers it with Sudanese staples like beans and lentils, or beef or tuna.

Al-Aldoum picked up pizza baking in a large restaurant in his home country Sudan, then took the craft with him to Libya when he fled, seeking asylum.

Eleven years ago, he arrived in Israel. Like tens of thousands of other African asylum seekers, he settled in the South Tel Aviv neighbourhood of Neve Shaanan, next to the city’s grimy bus station, and found work in restaurants. He draws Sudanese customers, but also neighbouring Eritreans, local Israelis, and others.

Adjacent to the restaurant is a bar that’s easy to miss from the street. Its entrance is through a blue metal gate, cordoned off by a tarp and barbed wire. The only way you would know it was there is by a rectangular sign above the gate showing a smiling woman exhaling smoke from a hookah. The entrance leads into a dim courtyard covered by a tent.

A few African men are sitting on plastic armchairs drinking coffee and smoking hookahs, while a handful of others sit at a table with a red-and-white checked tablecloth. Everyone is watching three TV screens showing, respectively, a pro wrestling match, a soccer game, and an action movie that looks like Top Gun, but isn’t.

Photos are not allowed. The owners do not give interviews.

Openness and suspicion, multiculturalism and insularity. These are two of the many contradictions that define Neve Shaanan, Tel Aviv’s diverse, underprivileged, and vibrant neighbourhood of asylum seekers, Filipino foreign workers, working-class Israelis, and others.

If Israelis hear about Neve Shaanan, it’s probably because of the debate over African asylum seekers that has occupied the country for years. By 2012, more than 60 000 people, mostly from Eritrea and Sudan, had entered Israel illegally through its border with Egypt. They say they are refugees seeking asylum from war and brutal dictatorships at home. But the Israeli government contends that they are economic migrants seeking jobs and a better life in a developed country.

Since 2012, the Israeli government has tried to keep out asylum seekers and remove those already in Israel. It has erected a fence on its southern border, placed thousands of asylum seekers in a detention facility in southern Israel, offered incentives for them to leave, and tried to negotiate deals with third-party countries to absorb them. By 2018, about 37 000 asylum seekers remained in Israel.

This year, the government struck a deal with the United Nations to transfer half of the asylum seekers to other developed countries, while affording the other half legal status in Israel. But Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu abruptly backed out of the deal amid objections from Israeli residents of South Tel Aviv, who have portrayed the asylum seekers as a threat to their safety and culture.

The changes in the neighbourhood have been jarring to some of the older Jewish residents who have seen groups of young Sudanese and Eritrean men move into apartments once occupied by Jewish families like theirs.

Although foreign residents, mostly African asylum seekers, make up the majority of residents of Neve Shaanan and its surrounding area, they accounted for less than a third of the crime rate from 2015 to 2017. Police have also beefed up their presence there. The station responsible for Neve Shaanan’s area grew from eight police officers in 2010 to nearly 200 last year – plus 50 border police officers.

Neve Shaanan exists in the shadow of Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station, a concrete behemoth that seems like it was designed by MC Escher on an off day. The neighbourhood’s streets are shaped in semicircles, intended to look like a menorah on the map, and combine small storefronts with crowded, dilapidated apartment buildings and some new gentrified developments.

They are also dotted with unlicensed bars like the one next to the pizza place, called hamaras, that police have been trying to shut down. A large, relatively well-maintained park is across the street from the bus station, where children play on a swing set and drug addicts lay by the curb.

According to Tel Aviv’s official statistics, Neve Shaanan has about 5 000 residents, part of a larger South Tel Aviv district with a population of 30 000. But the real number is much higher. An Israeli Knesset report from 2016 said that anywhere between almost 15 000 and 30 000 African asylum seekers live in South Tel Aviv – most of them in and around Neve Shaanan.

“The neighbourhood is very crowded,” said Haim Goren, who has lived in Neve Shaanan for 11 years. “It’s a neighbourhood where 20 000 people live, where 30 years ago it was 5 000. There’s friction when you have tons of people in a small area.”

The neighbourhood was founded in 1921 by another set of refugees – Jews fleeing anti-Semitic violence in the adjacent Jaffa. Funded by foreign Jewish philanthropy, they eventually built a row of orchards that supplied Europe with fresh Jaffa oranges. In the 1920s, Tel Aviv incorporated the neighbourhood and established its central bus station there in the 1940s, filling the streets with noise and pollution, and driving out anyone who could afford to move. So another set of refugees – recent immigrants to the new Jewish state – filled it up.

“Throughout the years, a disadvantaged population remained here,” said David Cohen, a guide who does historical and culinary tours of Neve Shaanan. “By the ‘60s this was one of the most severe neighbourhoods in Tel Aviv. Many of the apartments were empty, without renters. A lot of businesses closed, and that drew a lot of crime organisations.”

It was still a bad neighbourhood in the early 2000s when asylum seekers began arriving from Africa. Because Neve Shaanan was next to the bus station and so neglected – with abandoned apartments and few police patrolling the streets – it was an easy place for illegal immigrants to settle. Asylum seekers filled the neighbourhood. More than 40 000 came between 2010 and 2012.

They have consistently faced racism from locals, as well as national politicians. In 2012, a mob attacked African residents of South Tel Aviv. Miri Regev, now Israel’s Culture Minister, called them a “cancer” (she later apologised). Official government documents refer to them as “infiltrators”.

“We are not living here, we are surviving,” said Teklit Michael, an Eritrean asylum seeker who came to Israel in 2008 and has since become an activist, serving as a spokesman for his community and helping fellow asylum seekers secure their rights. “You don’t know what’s going to happen the day after right now. You have to live as you can, to be safe for the day.”

(JTA)