click to dowload our latest edition

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Published

3 years agoon

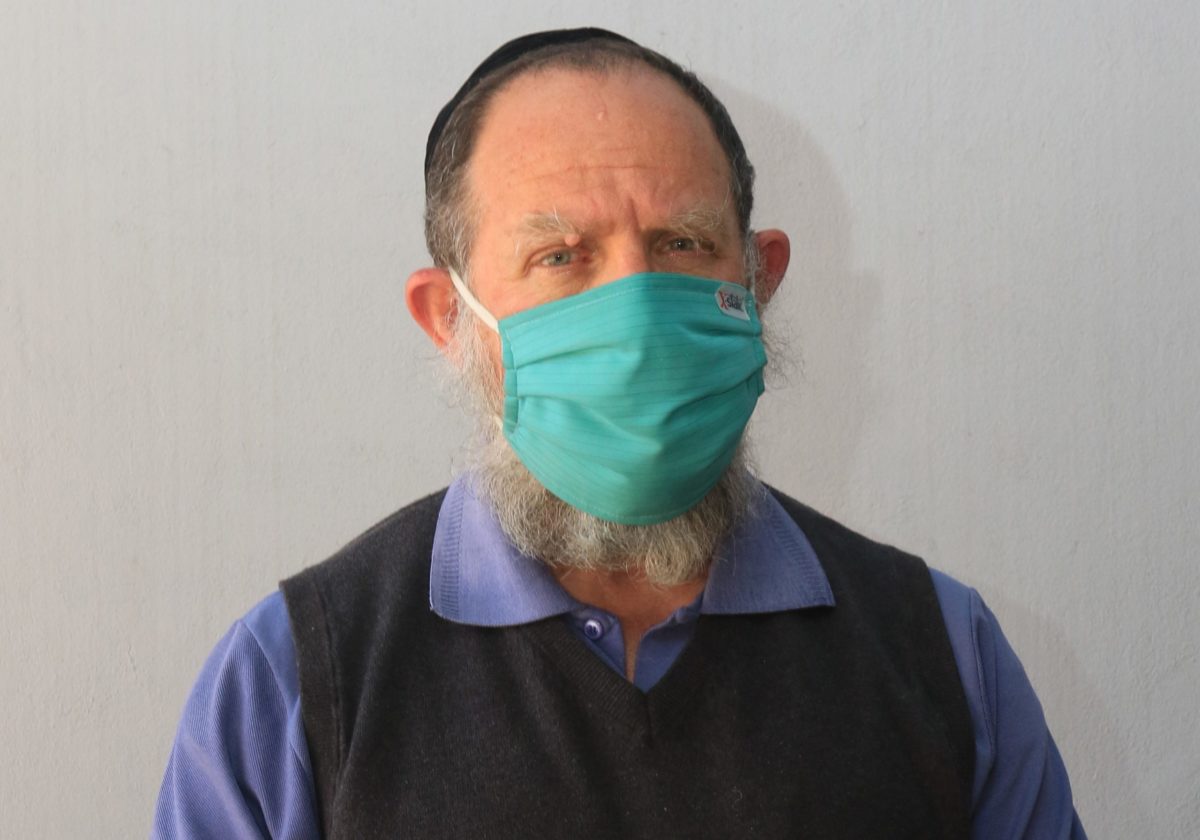

As the dust settles after the Mount Meron disaster, questions will be asked about how it happened and why. Local expert Professor Efraim Kramer says stopping stampedes requires training, expertise, and planning, as just one “spark” in a crowd can have deadly consequences.

“It’s complex, emotional, and difficult to talk about stampedes, because people die needlessly. Whether it’s a football stadium or Mount Meron, people are going there for joy, yet it turns into tragedy. There’s no real place for blame because it needs a full investigation,” says Kramer.

He shared his perspectives with the SA Jewish Report as an expert in emergency and mass gathering (event) medicine. Kramer is the former head of the division of emergency medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand, and professor of sports medicine at Pretoria University.

He has specialised in emergency, disaster, and stampede medicine for 30 years, and was FIFA’s tournament medical officer at the FIFA World Cup Russia in 2018. Since then, he has been actively involved with FIFA Medical. He is also involved in teaching and researching mass gathering medicine, including soccer-stadium stampede prevention and the management of disaster medicine, having been actively involved in assistance missions after earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, floods, and volcanoes.

“A stampede is a terrible way to die,” he says. “It’s a slow asphyxiation. You can’t breathe for two to four minutes. The weight of a crowd like that can push over a wall. It’s tons of pressure. Then, if people fall down, they have no time or room to get up, and others trample on them. People either walk [over those who have fallen] or fall over themselves. So you also see severe trauma injuries.”

Kramer says preventing stampedes requires legislation, management, planning, risk assessment, logistics, and most of all, training. “In almost every incident I’ve seen like this, there has been no training. You can have 1 000 policeman and 1 000 stewards, but if no one is trained to recognise the signs of stampedes, they can easily happen. All it takes is one ‘spark’.”

He alludes to one person falling over in a stadium passage, or one fight that broke out in a stadium, which led to many people dying in stampedes in the past.

Kramer explains that medically, responding to a stampede is often counterintuitive to what a medical professional would normally do.

“In other mass disasters, you triage people who aren’t unconscious and prioritise them over unconscious victims who you may leave. But in a stampede, you immediately do CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation] on the asphyxiated, non-breathing victims, because they usually have a healthy heart and you want to get oxygen back to that heart. You do CPR for half an hour to get the heart to start pumping again. You do CPR on every single non-breathing person, and then they do survive. So you don’t run it like an accident. You don’t take them to hospital – you work tirelessly on the scene.”

He says in crowded environments, it’s essential to keep the flow of people going. Even if they are walking in a narrow area, like the site where the Mount Meron tragedy occurred, as long as there is a flow of people, it’s likely to be safe. “But as soon as something goes wrong – like someone falling – it quickly perpetuates a vicious cycle.”

One way to keep the flow going is to use megaphones. “You can tell people to stop pushing, that people are getting injured, and to stay where they are. You can tell people that are being crushed to turn on their side, as then they can still breathe. You can control things verbally. Communication is crucial, and it needs to be planned beforehand.”

In his work with football stadiums, other small but significant changes have been implemented to prevent stampedes. For example, tickets are sold offsite to prevent stampedes should tickets run out. In addition, spectators are allowed only to sit in a seat, no one is allowed to stand or sit anywhere else. This controls numbers and keeps pathways open. “In 2021, crowd management is a science that needs to be learnt before disaster strikes and people die,” he says.

Kramer has seen similar numbers of deaths at other stampedes. For example, 43 people died at the Ellis Park Stadium tragedy [in South Africa] exactly 20 years ago. He says this number of fatalities is expected in the first five minutes of a stampede.

While Kramer wants to avoid laying blame, his first impression of the tragedy is that “the system went wrong … from the top, right to the bottom. Now, they’ll have to do what they should have done before – control the amount of people, manage risk, train personnel, and so on. It needs to be a well-oiled machine to stop people from dying.”