click to dowload our latest edition

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Published

7 years agoon

By

adminSUZANNE BELLING

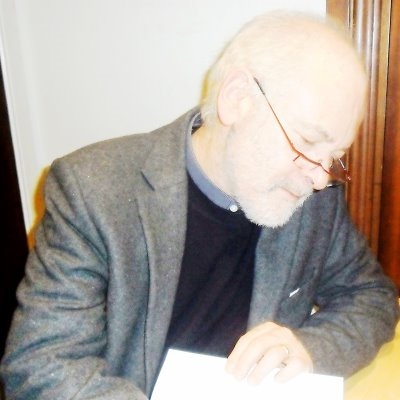

In conversation with Apartheid Museum curator, Emilia Potenza, at the Rabbi Cyril Harris Community Centre last Wednesday, he tells how he made this break based on the same ethical grounds which made him join in the first place.

These reasons included: “When people endorse Nkandla (Jacob Zuma’s homestead) and divert funds which are meant for the poor, what they are doing is rupturing the connection with the oppressed.”

The Zuma project entailed personal ambition and a breaking away from the values that underpinned the Struggle, according to Suttner, a researcher and social and political analyst, who is also an emeritus professor at Unisa and part-time professor at Rhodes University,

“Too many people who have been in the Struggle lack humility,” he said: “The values were ruptured and the experiences that they now embarking on are ones I want no part of.”

His specific reason for leaving party politics was the Khwezi rape trial (When she accused Zuma of raping her), when she “was treated with cruelty. We fought against cruelty. No member of the SACP or ANC said a word [against it] in public.”

Suttner’s leaving his former comrades was not easy. “I have a sense of loss and loneliness… but companionship relates to shared values and shared experience; these values were ruptured and the experiences they are now embarking on, are ones that I want no part of.

“It’s cold outside here, but what sort of warmth do they have inside there, where they got to negate everything they believe in?”

On the future of South Africa, Suttner posited that people mustn’t expect a messianic figure to be put in place at the end of the year and that everything will fall into place.

“I believe we have to look for commonalities between people who may never have joined together – the richest of the rich and the poorest of the poor – who have a common interest in clean government and legality.”

Advocating “baby steps”, he said South Africa should find a way of uniting people around limited goals, such as defending the Constitution, ending corruption and being led by unifying people who were non-party partisans – for example, religious figures.

“People are already out there on the streets defending the Constitution, but a lot of them are linked with returning the ANC to what they regard as its ‘true self’, a sort of romantic golden age.

“And they are not asking themselves: ‘Where did Jacob Zuma come from? What is it in the ANC that made this possible?’”

He had to ask himself these questions, because he had trained some of the young people who had voted for Zuma and regard him as only an aberration.

“We’ve got to rebuild wherever we are. If you are in the Apartheid Museum, you have a role to play with people’s consciousness. If you are a nurse, it is how you treat the patients. If you are a teacher, it is how you do your job. Are you drunk? Are you womanising…

“It’s part of a contribution to building an ethos different from the dog-eats-dog ethos of the present.”

Speaking on his joining the resistance to apartheid, he said: “To join the Struggle is to embody the pain of the oppressed in yourself.

“I grew up in the aftermath of the Second World War and experienced anti-Semitism. I asked myself when I looked round me and saw black people treated badly: ‘If anti-Semitism is bad, how can I condone what is happening to the black people?’”

Initially working on his own after coming back to South Africa in the mid-1970s, when he abandoned prestigious Oxford doctorate studies to return to this country and contribute to the Struggle, he was arrested in 1975 and sentenced to seven-and-a-half years imprisonment.

In a statement from the dock at the end of his trial in the Durban Supreme Court, he said: “I am not the first person, nor the last, to break the law for moral reasons. I realise that the court may feel that I should have shown more respect for legality.

“Normally, I would show this respect. I would consider it wrong to break laws that serve the community. But I have acted against laws that do serve the majority of South Africans, laws that inculcate hostility between our people and preclude the tolerance and co-operation that is necessary to a contented and peaceful community.

“For this I will go to prison. But I cannot accept that it is wrong to act as I have done, for freedom and equality, for an end to racial discrimination and poverty. I have acted in the interests of the overwhelming majority of our people…”

He was placed with the few whites who had been sentenced for their activities in the ANC, including, Rivonia trialist Denis Goldberg, who was serving a life sentence; the blacks convicted, who included Nelson Mandela, were sent to Robben Island.

After Suttner’s release, he resumed his activities and was arrested and sentenced a second time. After serving this sentence he was placed under house arrest in 1988.

He was severely tortured by the security police, including electric shock treatment. He was often subjected to verbal and anti-Semitic abuse as well.

“I heard some people held out for a very long time, but then told things they had never been asked, because they were so exhausted from the torture. As far as I knew, I was the first white to be given electric shocks.

“I was a Communist and they treated my being Jewish as equally criminal. They would say: ‘Hierdie Jood, ek gaan hom doodslaan – This Jew, I’m going to kill him’. It was almost interchangeable.

“There was widespread anti-Semitism among them, but it didn’t make things worse for me because they were going to torture me whether I was a Jew or not.”

Back to the present, Suttner was asked whether he was hopeful about the future in this country.

He replied: “I don’t think it’s helpful to be optimistic or pessimistic. I am not leaving South Africa. This is my country. “The thing with hope and good luck is, you have got to work for it.”

Klein

Jan 10, 2023 at 5:06 pm

A small handful of Jewish South Africans did good, while the vast majority stood by and did nothing.