SA

South African story told through the grapevine

Published

5 years agoon

By

adminMIRAH LANGER

The SA Jewish Report spoke to the editor of the book, Harriet Perlman, ahead of its recent launch at Montecasino in Johannesburg.

Perlman said that the roots of the project dated back to 2015. This was when two of her long-time collaborators, film director Akin Omotoso and producer Rethabile Molatela Mothobi, were approached by the Kalipha Foundation. The organisation’s Directors, Sithembiso Mthethwa and Manana Nhlanhla, had a somewhat unusual proposal.

“They were wine enthusiasts, and they wanted us to tell a story of South Africa’s transition to democracy through the lens of the world of wine, and the personal journey of black winemakers.”

Omotoso and Mothobi invited Perlman, who has worked in film, television, and print media for more than 30 years, to join them on the project. At the time, the plan was to produce a documentary only.

So began a period of extensive research, visiting wine farms, archives, and interviewing more than 40 key players across the wine sector.

The filmmakers decided to focus on four black winemakers. They were Dumisani Mathonsi, who had made the journey from rural northern KwaZulu-Natal to become the acclaimed white-wine maker at Adam Tas Cellars; Carmen Stevens who, growing up in Kraaifontein in the Cape Flats, had fought virulent racism to start her own label in the industry; Unathi Mantshongo, who shared her story of leaving Mthatha in the Eastern Cape for the chance to study at Stellenbosch University, ultimately becoming a viticulturist; and finally, Ntsiki Biyela, who growing up with her grandmother, Aslina, in a KwaZulu-Natal village, would later name her first wine brand after this beloved figure in her life.

“We wanted to hook the film around their personal journeys, and then weave in other stories about wine makers, wine in the black community, and experts’ [reflections],” said Perlman.

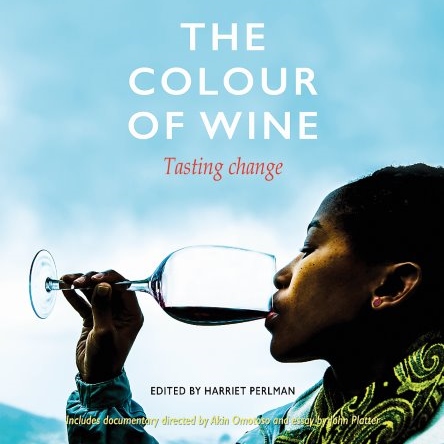

The documentary project did so well, the Kalipha Foundation asked Perlman to compile a book on the subject. “That was fantastic,” said Perlman, because it allowed her to deal with the material gathered for the documentary in more depth.

The original four winemakers remain at the core of the book. However, their stories are now enhanced by the evocative photographs of Mark Lewis.

Lewis travelled with each of them to their childhood homes. He then created a visual diary for each that captures their journey across starkly different South African realities.

Besides an extended number of interviews, and these photographs, Perlman has added into the book a number of new sources including historical essays, personal reflections – even recipes.

Yet, for Perlman, the individual stories of the winemakers remains the most moving aspect.

“Personal stories are still what matters most as we grapple with going forward. If you understand how people have navigated change and opportunities, then you can build a society,” muses the born-and-bred Johannesburger, whose early foray into the world of wine included sweet sips from the kiddush cup.

The stories of the black winemakers share two key threads. The first is the racism they faced in trying to pioneer change in a largely untransformed industry.

“Their stories reveal that the history of wine has its own ugly apartheid past, and that trying to transform that is complicated and difficult,” Perlman said.

The other key thread is that, somewhere along the way, each of the four did connect with mentors and teachers who helped them harvest hope for the future.

For Perlman, the power of these relationships was one of the most surprising take-away insights gained from the project:

“Teachers matter! There are so many big challenges and problems and questions. But actually doing your bit and being a caring, respectful, nurturing teacher matters.”

Speaking at the launch of the book were two of its main protagonists, Biyela and Mantshongo. Both entered the wine industry after taking up full bursaries at Stellenbosch University. However, they admit that before they arrived, they knew nothing about wine, and certainly nothing about speaking Afrikaans!

“Winemaking? I had no idea what they were talking about. It could have been anything. All I could see was an opportunity to change my life.” said Biyela.

As she began to face the reality of being in a completely alien environment, Biyela confesses that “there were a lot of tears and crying all the time, but then at the same time, there was perseverance. I told myself that there is no other option.”

Coming to Stellenbosch was a similar culture shock for Mantshongo:

“You are like a ghost. Nothing is designed for you. When you go to [the student] res[idence] to pick your meals, you have never heard of the food on the menu. When there is a vergardering (a meeting), you have no idea [why the people are gathering]. You think there is a fire, and you grab your ID.”

However, it did eventually get better for both of them. Biyela quipped that one of her survival skills was learning how to sokkie (dance).

For Mantshongo, it was surviving her first sip of wine.

“I had studied for a year and a half before we actually tasted any wine. It was such a build-up. There was a whole ceremony … Then you take a sip, and you look around the room. The emperor is naked! You are just waiting for someone to jump up and say, ‘This is a joke!’” Mantshongo said that she decided on the spot that was why “people spit this thing out – It’s disgusting!”

Also speaking at the launch was wine expert Michael Fridjhon. He said that since the turn of the 20th century, alcohol had been used as a means to drive people into the cash economy.

The height of this social manipulation was during apartheid – not just through the infamous “dop” system (paying labourers with cheap wine) – but also in how the government positioned itself as “the bootlegger… [supplying] alcohol in the townships to fund the apartheid machine”.

These historical realities and the personal hardships those like Mantshongo and Biyela experienced were not just “deep, dark history”, said Fridjhon.

Instead, they were issues that needed to be addressed in contemporary society in order to free South Africa to be able to enjoy a relationship with alcohol without elements of abuse.

“Wine, in the responsible way, leads to human engagement. Wine is consumed around the table, and if you are going to stay around the table, then you are going to have to get past your differences. Wine offers valuable facilitation, and it touches the human spirit,” Fridjhon declared.