Featured Item

Tackling bullying starts with tearing down its superstructure

Published

8 months agoon

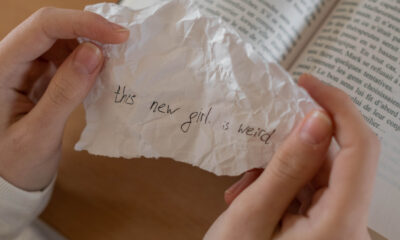

From WhatsApp groups to social media platforms, there is no respite from bullying in our increasingly interconnected world. Yet what’s bullying doing to our children, and how can understanding its complexities help to create meaningful change?

Educational psychologists Marina Bezuidenhout and Naveshini Thumbiran recently led a discussion on the intricacies of bullying, hosted by Chevrah Kadisha Community Social Services at The David Lopatie Conference Centre in Johannesburg.

Bezuidenhout said the scars from bullying could cause “genetic trauma”, passed from generation to generation. “Many studies have been done that show it’s the same fears, the same anxieties, which come through the generations,” she said.

Though about 20 years ago, bullying was predominantly a physical phenomenon, today it’s more insidious and underhanded, she said. “There has been an immense shift with the inception of social media. You cannot leave the bullying where it happens and have some kind of respite from it.” The ongoing sense of isolation this breeds is increasingly prevalent, especially among teenagers. Today, Bezuidenhout said, cybertechnology has become one of the leading causes of suicide. And only one in five cases of bullying are actually reported, so what happens when it remains undetected?

Focusing solely on helping those being bullied is, however, also a problem in that it puts the whole responsibility on the victim, said Bezuidenhout. They begin to feel like they’re the problem, and that they have to do the work needed to bring about change. Bullying is, in fact, a systemic problem and we need to understand all the people who make up that system.

Dismantling the structure underpinning this system begins with understanding the impact of bullying on the victim. Bullying causes increased absenteeism in school and illnesses as a physiological response to prolonged stress. “We see children who are extremely bullied at school who start having epileptic fits, but nothing shows up on scans,” said Bezuidenhout.

“Yet, you can actually see the trauma that comes through and when we deal with the bullying and the mind-body connection, and it starts to feel better, all the symptoms eventually subside.” Left unchecked, bullying can lead to depression, anxiety, and even suicidal ideation, an increasing concern. “‘Bullycide’ is now the word that they have coined for suicide as a result of bullying,” she said.

The bullies themselves are often not who you’d expect them to be, Bezuidenhout said. They’re no longer just the oafish or strange kids or the jocks. “It can be a popular child; someone the teachers really like and see as the golden child. They often get away with this murderous kind of behaviour because people don’t see them for who they truly are.” Bullies are also often risk takers, and may suffer from conduct disorders. “They often feel rejected by their peers.”

Ironically, the group that sometimes struggles most with bullying is the bystanders, Bezuidenhout said. “They’re too scared to do something. If they do get involved, they can often be rejected. Sometimes they think it’s better to observe or to say nothing, but that traumatises them in and of itself because they feel they didn’t do anything to help the victim.”

Bezuidenhout also spoke of kids getting away with highly inappropriate behaviour because of no discipline at home or at school. This lack of structure perpetuates bullying because these children think they can do whatever they want to with no consequences.

“Bullying is a normal part of growing up.” “You’ll get over it.” “It will stop if you ignore it.” Collapsing these and other myths surrounding bullying, Bezuidenhout said that children must be taught to respond rather than react to bullying. It’s about saying things like, “I don’t like what you’ve said to me, if you say it again, I’m going to tell someone,” or “Let’s go and tell on together,” which often alarms the bully.

“One of the most powerful things to teach a child,” she said, “is to diffuse a situation rather than to retaliate emotively. So, if the bully says, ‘You’ve got a really big nose,’ you say, ‘Isn’t it just beautiful?’” Bullies look for victims who are going to be reactive, but if you diffuse it, it goes away.”

We need to teach our kids the difference between conflict, playful banter, and bullying. “Bullying is repetitive behaviour,” Bezuidenhout said. “It’s intentional and purposeful in order to hurt, and it causes a power imbalance.”

Bullies tend to shift blame and become defensive when confronted, she said. They won’t take responsibility and they’ll blame the victim, who often feels like they have to be “less than” in order not to antagonise the bully. “Kids who bully are actually extremely perceptive and excellent observers of behaviour. So, they watch, they know exactly who’s going to be a possible victim of bullying.” That’s why projecting confidence through something as small as maintaining a good posture or eye contact is so important.

Bezuidenhout also stressed the need for schools themselves not to become bystanders as a result of being scared of upsetting parents. Schools cannot be complacent. They also must teach student bystanders to be upstanders by telling the bullies to stop their behaviour. “Once we diffuse the fear and the attention, there’s nothing to feed off.”

Practical suggestions also include having a bench where someone who feels alone can sit, so that peers can then join or include them; or having a post box for kids to share their experiences of bullying with teachers. They can then respond, which helps the child feel less alone. “It’s the isolation that causes things like suicidal ideation – that’s where it’s dangerous,” Bezuidenhout said.

“Where we come from plays a huge role in whether we become bullies,” Thumbiran said. “Whatever we hold in terms of toxicity spreads through our interactions.” It’s also about showing our kids the right way to behave through our own actions, said Bezuidenhout. They internalise what we do, not what we say.

Parents also need to be attuned to what’s going on with their children. If they tell us about incidents of bullying, we must ensure that they know they are heard, supported, and that we’ll take appropriate action. Ask your children what they need from you in such situations.

We also need to empower our kids to find themselves and own their identity. “Often bullies and victims struggle with belonging,” Bezuidenhout said. “Belonging isn’t the same as fitting in.” Kids who will do anything to fit in will behave in ways that they shouldn’t. She quoted professor and author Brené Brown who said, “Fitting in is about assessing a situation and becoming who you need to be to be accepted. Belonging, on the other hand, doesn’t require us to change who we are; it requires us to be who we are.”

Pam

Sep 16, 2023 at 9:10 pm

Look no further than the parents of the bullies – where do you think these children learn this behaviour? I have grown, elderly Jewish men woman, clusters of them in the community, people who are respected by their peers and thriving in the community who systematically and for years have been bullying me, people in position of power, it’s like a cancer. It turns my stomach when people cry anti-Semitism, why are we persecuted as a race? Maybe because there are those that persecute their own. Sickening. Absolutely shameful. A disgrace to G-d.