click to dowload our latest edition

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Published

3 years agoon

By

Jordan MosheAuschwitz, Treblinka, and other European concentration camps are familiar to most of us, but few of us know about those that operated during World War II in Africa.

These were, in fact, run along scarily similar lines, but the stories of those imprisoned there are hardly known.

This historical insight was shared at last week’s online Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony hosted by the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre.

Survivors’ testimonies, a moving poetry recital, and various addresses marked the 76th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp by Soviet forces on 27 January 1945.

Keynote speaker Aomar Boum, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that European Jews, non-Jews, Muslims, and Christians were interned in African camps.

“North Africa, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya came under three regimes of colonialism from France, Spain, and Italy. As the war went on, these three had colonial presences in the region and created camps of their own.”

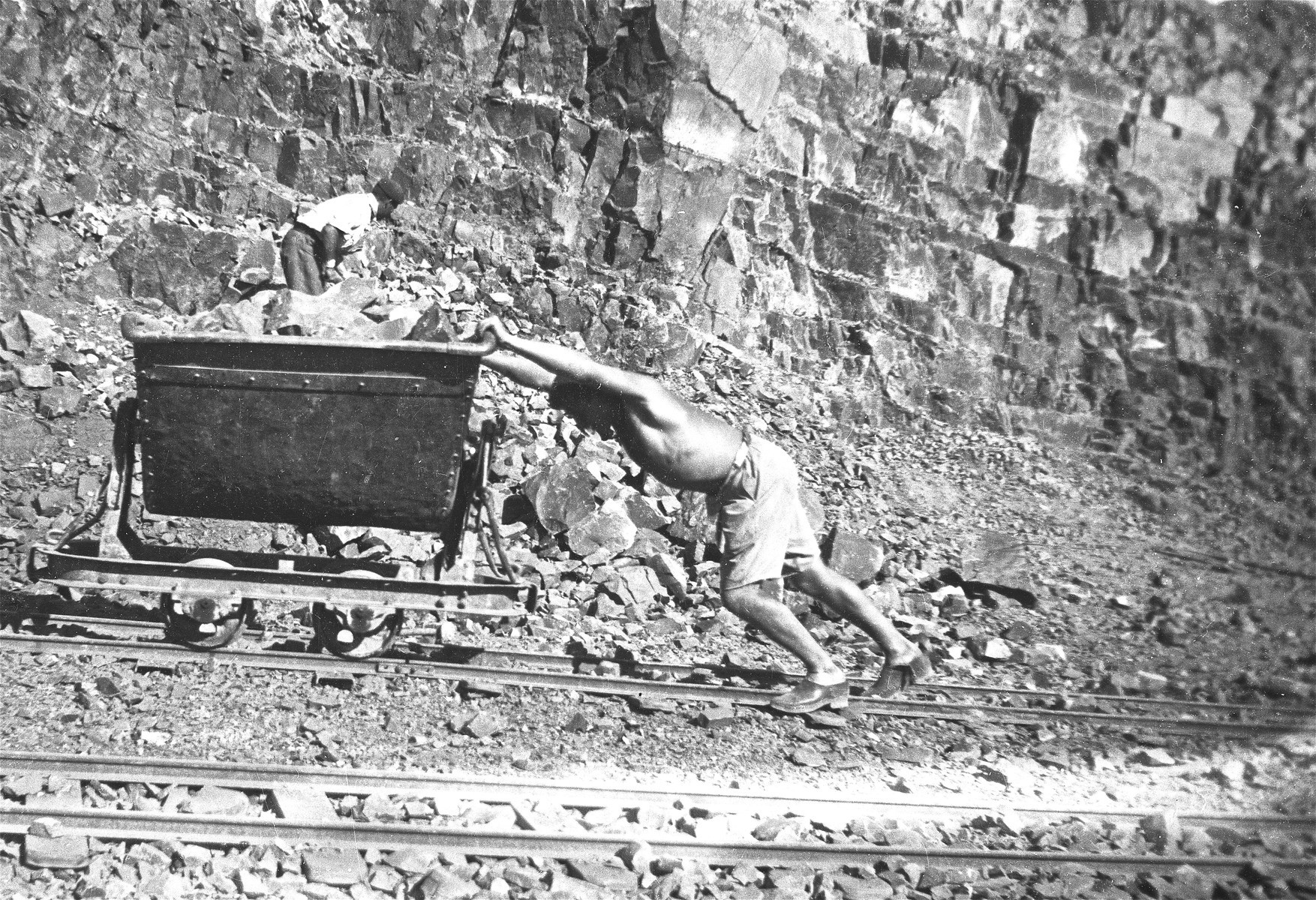

According to Boum, a network of penal, detention, and labour camps was established across the region in the 1940s to serve the needs of a railroad project that had been launched in the previous century.

In 1941, Nazi-allied Vichy authorities transferred hundreds of refugees to the Saharan camps, many of them foreign Jews and other “undesirables” who had sought shelter in the region. Others had survived the Spanish Civil War, ending up as displaced persons in Africa only to be taken captive and held in the camps.

“The camps were linked to the colonial project of the 19th century, when France wanted to establish networks of railroads to connect the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa,” Boum said. “In the early 1940s, the colonial Vichy administration set up networks of forced labour camps in Algeria and Morocco to build the railroad system, and they relied on refugees who had come from Europe.”

The Nazi regime also supported the project, seeing an opportunity to exploit the natural resources of the region, which were mined by detainees.

Although not strictly death camps, the Saharan camps were notorious for their harsh conditions, Boum said.

“There was nothing around for miles, nowhere to go, and nowhere to flee,” he said. “In the middle of the desert, there was no need for walls or wire. Nature was used to subdue internees and make sure they followed orders.

“Even after the Americans landed in North Africa, some of the camps remained open until 1944. American Jews put a lot of pressure on the American government to close the camps, but it wanted to keep them as they were until it defeated the Nazis.

“As a result, internees spent time in the camps even after the Americans landed in the region.”

Unlike the camps of mainland Europe, not much information has survived about what happened in these camps, Boum said, and most records were actually kept by inmates themselves. Drawings, journals, and poems are some of the few remaining pieces of evidence of what transpired, making preservation of this history especially pressing.

“This is a story we don’t know a lot about but which needs to be written,” said Boum. “As survivors are dying, we have to find ways not only to collect their stories but also to preserve the spaces [in which they were held].

“Some camp buildings have survived, as have some of the railway lines. We need to ensure that these sites become memorials as well.”

Martin Schafer, the German ambassador to South Africa, said he had tried so many times to understand burning questions about the Holocaust. “How did we Germans, a people proud of their cultural heritage and humanity, become murderers? What did it feel like to be a perpetrator or, more importantly, a victim?”

Schafer said he had failed to answer these questions, but the current pandemic might offer a glimmer of insight.

“I have never been persecuted or oppressed, so I cannot try to understand what it meant,” he said. “But the fear of being struck down at random and dying, is that not something we can feel in this pandemic?

“It’s not comparable to the experience of those who suffered during the Holocaust, but perhaps I can feel something of the fear that your children, parents, or friends are here one day and gone the next, never to come back.

“Maybe, for this one time in my life, I get a little glimpse of the fear and anxiety that gripped Jews and others after 1933 in Germany.”

Alternative facts, extremism, fascism, and antisemitism are on the rise, Schafer said, suggesting that mankind has learned nothing from the past.

“Parts of the world in the weeks we have gone through resemble my home town of Berlin in 1929, when the brown masses were on the streets, when politics descended into the abyss and no one knew what was to come.”

As a representative of Germany, Schafer vowed to commemorate those who perished in the Holocaust and ensure that history didn’t repeat itself.

“We will not let it happen that fascism, racism, and hatred invade our hearts and minds,” he said. “We are willing to fight.

“The German nation will be ever conscious of our guilt and responsibility, and we will do everything we can so that the horror the Shoah is never repeated.”