OpEds

Sharpeville and Sobukwe: the day the world turned

Published

1 year agoon

There’s good reason why South Africa’s Human Rights Day is also the world’s International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. At Sharpeville on Monday, 21 March 1960, the police killed 69 people protesting against pass laws. The massacre transformed South Africa, and overnight, created international hostility against apartheid.

On that day, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) called for black people to leave their passes at home and go to the nearest police station and demand to be arrested. Not carrying the dompas was a crime and meant instant arrest.

Aprt

Aprt

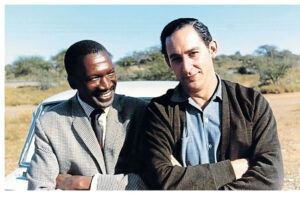

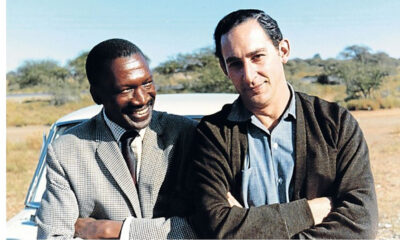

I went to see him at 05:30 that morning at his home in Mofolo in Soweto. Not only was I a reporter on the then Rand Daily Mail, but we were already close friends. We had liked each other the moment we met. As my wife, Anne, later described him, “A tall, elegant man with such life and kindness shining in his face.” He had a natural charisma, and with his fierce commitment to freedom, was a powerful speaker at meetings.

He had proved his leadership capabilities in heading the student representative council while doing a Bachelor of Arts at Fort Hare University. His speeches urging African nationalism had become legendary.

He was the obvious choice to lead the PAC. The movement was less than a year old, after a breakaway from the African National Congress (ANC). The Africanists, noted for belief in the continent’s unity, had accused the ANC of failing to carry out its policy of non-collaboration with the oppressor adopted in 1949.

The PAC was ignored by whites. It was seen as anti-white, a view fostered by ignorant white newspaper commentators (although, to be correct, some members were that). Sobukwe was a nonracist to his core. He said, “There’s only one race to which we all belong, and that’s the human race.”

Sobukwe had told me about his intention to launch a mass campaign against the passes. We had also talked about his personal struggle: he enjoyed unusually high status and income because he was a “language assistant” teaching Zulu at the University of the Witwatersrand.Robert

But he faced a hard critical decision: Rhodes University had just offered him a full lectureship. For black people, it was ground breaking, and would provide him with a sedate and stable academic life. He agonised, then accepted that his role was to serve his people, whatever the cost. He said no to Rhodes and resigned from Wits.

In calling on people to get arrested, he again proved his leadership by announcing that he would go first. That’s why I was with him that Monday morning, and followed him and a dozen other PAC members, walking the 4.5km to Orlando Police Station. About 200 other PAC members were also there. The officer in charge told them to wait outside the wire-mesh fence.

In mid-morning, word came that the police had shot and killed people at Bophelong, an hour’s drive away. I told Sobukwe. He was deeply upset. He had called for non-violence, and had urged this on the police.

At Bophelong, an air force Harvard propellor plane was flying low, close to telephone poles. People were at first frightened but then angrily shook their fists as it roared overhead. Policemen were there with Saracen armoured cars, which had recently come into use. I heard they were going to a township called Sharpeville, near Vereeniging. I had never heard of it.

I followed them, with a photographer, Jan Hoek. The police ordered us to leave the township, but we stayed and I drove inside the crowd of about 5 000 – the police said 20 000 – surrounding the police station. Contradicting what the police later claimed about the crowd being threatening, I had no trouble. I sat on the pavement and when people learnt I was from the Rand Daily Mail, they were eager to tell me about their suffering from the pass laws which controlled every aspect of their lives, and their hardship because of poverty-level wages.

After a while, I drove around the crowd and, suddenly, the crackling gunfire. We saw bodies covering the ground. A minute or two later, we were surrounded by a crowd which had become a mob: they battered the car with rocks and sticks. I managed to break through, bumped over the veld until I found a tarred road, and got back to Johannesburg. I was lucky, with only a bloodied ear. The car was a write-off.

That was the Sharpeville massacre. Immediately afterwards, Sobuwke and his men – no women took part – were arrested. It proved to be his last day of freedom until his death 18 years later.

Bold and brave as was Sobukwe’s “positive action” against passes, he had seriously over-estimated popular support. The PAC was new, and there was also mass intimidation in the police and employer threats.

Sharpeville was one of the few places where large numbers responded to Sobukwe. Another was Cape Town. But intense anger spread. On Friday, the frightened government suspended pass-law arrests. Never before had black protest led to such a government retreat.

The ANC stepped in. Its leaders publicly burned their passes, and called for a nationwide strike (which was illegal for black people and thus called a “stay-at-home”). South Africa was on fire. The government rushed laws through parliament banning the PAC and ANC, and then declared a State of Emergency. During the next eight months, 1 600 people of all colours were detained without trial for past and current political activity; 18 000 black people were detained as “vagrants”; and many landed up as abused labourers on farms.

Sharpeville proved to be a dramatic turning point for South Africa. There was the tragic loss of life. And the black resistance which followed was met by ever-harsher repression. The Afrikaner Nationalist government went down the road to authoritarianism: the all-powerful Bureau for State Security; unbridled army power; assassinations; and the cruel 1980s and early 1990s, until democracy was finally achieved in 1994.

Sharpeville also changed the world outside. The massacre was headline news, and South Africa became a focus of interest and abhorrence. Anti-apartheid movements sprung up. Protests and demonstrations became commonplace. Countries became hostile. The United Nations passed resolutions to impose sanctions on South Africa.

In 1966, the United Nations General Assembly declared that 21 March be observed every year as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. For South Africans, it’s Human Rights Day to remember those who died to fight for democracy and equal human rights.

Sharpeville was also the start of Sobukwe’s travails. After the massacre, he was charged with incitement and served three years in jail. As his sentence was ending, parliament enacted a special law called the “Sobukwe Clause”. He was put into virtual solitary confinement on Robben Island. They feared him that much. He was released after six years because of ill health. But it was into another confinement: banishment and house arrest. Nothing he said could be reported.

He died from lung cancer nine years later, in February 1978, aged 54. The restrictions on his movements delayed a medical diagnosis; otherwise he might have lived longer.

We had grown closer. I was allowed to visit him a few times in Pretoria Central Prison and on Robben Island. I visited him in Kimberley, always alone with him so as not to transgress his bannings. He studied and became a successful attorney, known as the “social-welfare lawyer” because he charged the poor such low fees.

I always thought of him in words from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: “A parfit gentil knight.” He was denied the national credit he deserves, and has been largely whitewashed out of history.

- Benjamin Pogrund was deputy editor of the Rand Daily Mail. He now lives in Jerusalem. His books include: “Robert Sobukwe: How Can Man Die Better” and “Drawing Fire: Investigating the Accusations of Apartheid in Israel”.

yitzchak

Mar 25, 2023 at 6:51 am

His assigning to the rubbish dump of history is a machination of the ANC who have never acknowledged Sobukwe.

Has he been honored anywhere?

(An APLA a day keeps Dr ANC away)