OpEds

And still, we have not lost hope

I found myself alone in Naryshkin Park, in Žagarė, a tiny village in Lithuania on a misty October morning, carrying a backpack heavy with stones and candles.

There were signposts for the alley of Linden trees and the chestnut tree grove, but not a single one for the “pit” as the locals call it, the mass grave on the edge of the estate which is where I was headed.

It was my second day in this village from which my father’s parents immigrated to South Africa in 1926. In the weeks leading up to my trip, I delved into historical research, the unbearable details of which still clung to me.

My plan was to stay no longer than was absolutely necessary to do right by my ancestors. I would make a clinical visit to say Kaddish at two murder sites – the park and town square.

I couldn’t gauge the protocol for such a trip. Was it appropriate to stay in a lovely hotel inclusive of breakfast? Have a massage or a moment’s frivolous retail splurge? Would I cope alone with the weight of what I was about to witness? When I fretted to my husband he’d said, ‘Just take it one pogrom at a time.’

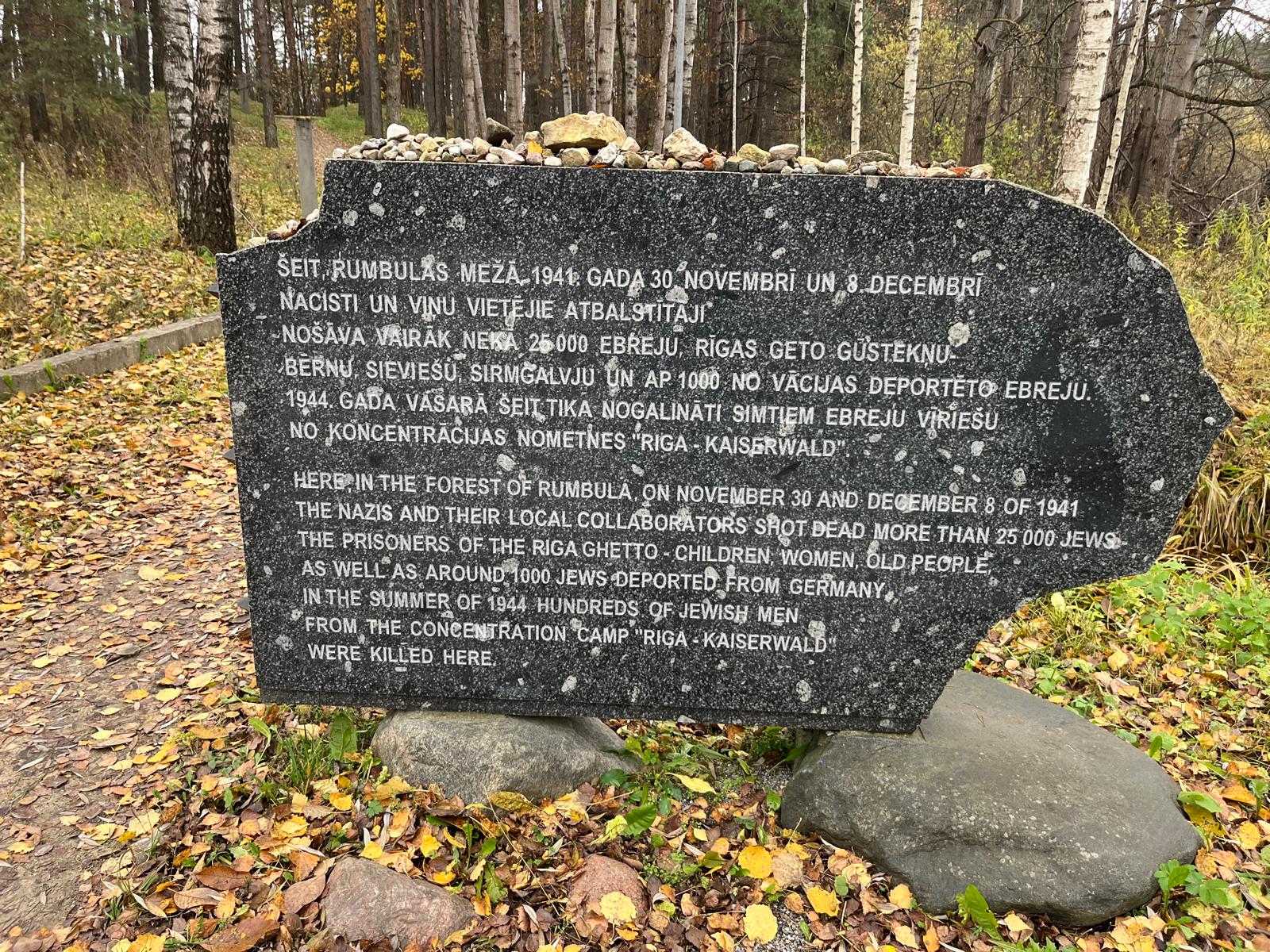

I’d already been to Rumbula Forest near Riga, where on 30 November and 8 December 1941, 25 000 Jews were shot and buried in a mass grave; and the concentration camp, Salispils, near Riga, now the site of enormous, moving sculptures.

This was my third stop – different, because my grandmother’s parents, sister, brothers, and nephews lie buried here with about 3 000 others. My father’s mother, Chaya, was the sole survivor of her family. After she’d left Lithuania in 1926, she’d never returned. She grieved afar from the shores of Africa.

Despite the absence of signage in the park, the village of Žagarė itself, with its ramshackle houses, and bridges over the river Svete, had unexpectedly, against all my instincts, enchanted me. The day before, I had located the little blue house my grandmother had lived in, with a well in the unkempt garden and goldenberries and grapes growing on a vine along the fence. Here was a relic of where life had happened before death stormed in; and my heart had opened like a lotus flower. I wanted to not love the place. But my felt sense, this is where my people come from, claimed me.

Eventually, Google Maps led me to a cordoned off spot at the edge of the park. I approached the single memorial headstone with Hebrew writing with slow steps as if entering a holy place. How benign this morning was, with me and my backpack, and yellow autumn leaves lying everywhere. I fell to my knees and rested my hands on the headstone. I tried to imagine the fear and terror of those who were rounded up, not by Nazis, but by their Lithuanian neighbours and herded to this spot where an enormous pit had been dug in preparation for what was to follow.

It was erev Yom Kippur, 1941. The reports are that they walked to their deaths, singing Kol Nidrei. Non-Jewish neighbours had turned on their Jewish ones, families they’d traded with at weekly markets and lived besides for generations. Ordinary Lithuanians drove their fellow Jewish citizens whom they blamed for aligning with the despised Russian Empire to this shadowland and opened fire on women, children, the elderly. They covered the writhing bodies with lime and soil. The pit, it is said, heaved for days afterwards. The townspeople continued to live in Žagarė as before, except Judenrein (Jew-free).

Before 7 October 2023, this might have all seemed incomprehensible to me. Now, not so much.

I wept, lit candles, said Kaddish, placed stones, and read Psalm 23, winding the words around myself like a shielding cloak. I looked up into the innocent trees and sang Hatikvah to them, my voice breaking on the words, “Od lo avdah tikvateinu” (and still, we have not lost hope).

The next day, the young mayor of Žagarė opened the old synagogue for me, which is now used as a concert hall, as well as the mikvah, still used as a public bath house.

I asked him how it is possible to build a new future in a place with such a dark past. “I don’t know,” he responded, “but having people like you, with ancestral ties, return here, is part of the story of reconsecration.”

Not a single Jew remains in Žagarė when once, there were thousands. The last one died in 2014. I guess it’s a hard sell, Žagarė, whose town square once ran crimson with Jewish blood. There, I did the same ritual as I’d done in the park.

My next stop was Liepāja, a town on the coast of Latvia, where a cousin flew from London to meet me. Here members of our family on my grandfather’s side had tried to flee, but were murdered, likely shot on Skede beach or in Rainis Park. These slaughters took place in December 1941 by local Nazi collaborators. Photos were recovered, which you need to brace yourself to see. Tourists came to watch as Jews were made to strip, stand, six at a time, on planks over the mass grave, and shot. I love the ocean, but this godforsaken beach shrieked with silent despair.

A week later, I was at the Nova festival grounds in Israel, where thousands of tourists wove in and among the memorial banners of those who were gunned down by Hamas terrorists. Fortified with remote history deep inside my bones, I once again walked through the valley of the shadow of death, strengthened, not weakened with each Kaddish I recited, each repetition of Psalm 23.

Yet none of this prepared me for what was to come when four weeks later, I was standing on Bondi Beach in Sydney, my new tattoo still too fresh for me to swim with. My friend, Jessy, had narrowly escaped the Chanukah massacre on 14 December with her five-year-old daughter.

On my right forearm in Hebrew, the words from Psalm 23 are inked, “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me.’”

As Jews, we are fated to traverse this valley in every generation. When we march, it’s not in performative protest across harbour bridges, but to our mass deaths. Perhaps the most compelling defiance of evil is to die singing G-d’s name. For whenever Jews are murdered, something holy at the heart of humanity is destroyed and the light of the world dims.

‘Od lo avdah tikvateinu…’ (And still, we have not lost hope.)

- Joanne Fedler is the internationally bestselling author of 16 books. She is a writing mentor and open water ocean swimmer. www.joannefedler.com. Her Substack is Angels in the Architecture.

Alfreda Frantzen

January 29, 2026 at 9:43 pm

Joanne, your story moves me to tears. These acts are incomprehensible. Cannot even try to understand. Truly, animals are angels compared to that type of human.

Miriam Bloom

February 4, 2026 at 11:55 pm

My father’s eldest brother, Mattityahu (Mattes) Segal z”l was transported from Siauliai (Shavel) Ghetto to Zagare, probably with many other victims, and murdered in the Aktion as mentioned in this memorial. His wife, Golda, together with her children, were transported to Stutthof concentration camp with the rest of the prisoners in Siauliai ghetto. Golda and her children were murdered in Stutthof. There were survivors, one of whom was Grunya Zilber z”l who gave her testimony to Yad Vashem. My father and five siblings had left for South Africa in the 1920s. Dora Love (z”l) also survived Stutthof and worked to educate adults and children about the Shoah. She is memorialised in Colchester UK, having moved there from South Africa. Thank you for this moving remembrance.