Banner

Spoke in NY & ate with Jewry in Brussels

Published

10 years agoon

By

adminHOWARD SACKSTEIN

Reprinted with permission, originally published under the title: “The day a nation voted – by HOWARD SACKSTEIN” in a 90th birthday tribute book titled: MADIBA – A TRIBUTE FROM SA JEWRY

The day a nation voted

It was a warm Sunday afternoon on 11 February 1990. Judy Froman, Kevin Joselowitz and I were watching the endless delays on SABC TV waiting for Nelson Mandela to walk free from Victor Verster Prison, in Paarl. My mind raced back to my legal principal at Werksmans Attorneys, Dov Judah, who had repeatedly warned me against campaigning for Mandela’s release.

Judah had been at Wits University with the then young Mandela, and he had been unimpressed by Mandela’s participation in class and his dedication to the law.

Judah had been at Wits University with the then young Mandela, and he had been unimpressed by Mandela’s participation in class and his dedication to the law.

RIGHT: from left, Howard, Madiba and Bantu Holomisa engage with a Jewish leader in Brussels

Judah was not alone, for many in our community, this would be a day of great uncertainty and disquiet.

As Madiba walked free at about 4:15pm, hand in hand with Winnie at his side, crowds shown on TV erupted into spontaneous jubilation. The northern suburbs of Johannesburg, were however, eerily silent. Judy, Kevin and I climbed into my car and headed straight to Hillbrow. On the streets of the inner city thousands of people ululated, danced and sang in a frenetic explosion of euphoria. Up and down Pretoria Street and Kotze Street all of us, waving leaf covered branches, toi-toi’d, sang and screamed until we were too exhausted to continue.

Poor planning left him homeless

After addressing an overflowing crowd of more than 50 000 people in Cape Town, Mandela flew to Johannesburg. Much of the release was poorly planned and Madiba had nowhere to stay upon his arrival in Johannesburg.

ANC activist Jean de la Harpe was assigned the responsibility for finding Mandela a place to sleep for the first few nights. She immediately called Barbra Buntman, a renowned Jewish anti-apartheid campaigner and chairperson of the Five Freedoms Forum (the umbrella body of white anti-apartheid groups). Barbra was ecstatic about the choice of her home for Madiba, but was forced to decline because her husband’s relatives were visiting from the UK and she had nowhere else to put them.

With the Buntmans out of contention, Mandela moved into the home of Sally Cohen. Jean later told the story of how they ran out of food in the house and she was instructed to go shopping for the Mandela entourage.

With the Buntmans out of contention, Mandela moved into the home of Sally Cohen. Jean later told the story of how they ran out of food in the house and she was instructed to go shopping for the Mandela entourage.

Groceries thrown over the wall

In the chaos and confusion of the time, Mandela’s security refused to allow Jean and her shopping back into the house. Desperate to get the food to Mandela, Jean threw the bags of groceries over the wall of Sally Cohen’s home.

LEFT: Present SA Ambassador to Israel Sisa Ngombane and Howard Sackstein catch up in June – their first meeting since Brussels

The excitement of the release was soon dampened when Mandela met with Yasser Arafat, hugging the guerrilla leader and declaring that he was not concerned about offending “the powerful Jewish community”. For those of us in the leadership of Jews for Social Justice (the Jewish anti-apartheid movement), Mandela’s actions jeopardised the thawing relations between the ANC and the organised Jewish community we had worked so hard to achieve.

Over the previous few years, Jews for Social Justice had facilitated dialogue between the Mass Democratic Movement and the Jewish community. In 1989, JSJ had sent a Jewish delegation to meet the ANC in exile in Lusaka. The Jewish delegation included Ann Harris, wife of the then Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris.

After the Mandela comments, former political prisoner and my co-vice chairperson of JSJ, Maxine Hart, immediately called one of Mandela’s chief aides, Terror Lekota. Together we facilitated a meeting between Lekota and representatives of the organised Jewish community. My parents, Maurice and Helen offered their home as the venue for the meeting. My memories of the evening are, however, marred by our family dog trying to bite Terror Lekota upon his arrival.

After the Mandela comments, former political prisoner and my co-vice chairperson of JSJ, Maxine Hart, immediately called one of Mandela’s chief aides, Terror Lekota. Together we facilitated a meeting between Lekota and representatives of the organised Jewish community. My parents, Maurice and Helen offered their home as the venue for the meeting. My memories of the evening are, however, marred by our family dog trying to bite Terror Lekota upon his arrival.

LEFT: Howard 2013-style, less hair, less intense and always in party-mode – at the Absa Jewish Achievers event which he has run for the past 3 years

For the rest of the evening, the dog and my parents remained banished to the bedroom as the parties met. Lekota, who had close ties to many of us in JSJ, understood the fears and neuroses of the Jewish community and promised to ensure a symbolic act by Mandela to re-assure the community of their welcome place within a soon-to-be changing South Africa.

Within no time, Mandela summoned Helen Suzman and Isy Maisels to his bedside in hospital to pass on a message of comfort to the community. Mandela’s words of reassurance were widely publicised within the community and went some way to allay their fears.

Later on, the diminutive and spunky Maxine Hart, never afraid to confront the apartheid government or a struggle icon when she thought he was wrong, would meet Mandela at a private party and lambaste him for the thoughtlessness of his comments.

Euro-Jews wanted to host Madiba

In early 2003, I received a request from the World Jewish Congress’ European political arm, they wished to host Mandela at a function in Brussels. I assured them the request was impossible but they were persistent. Months and months of negotiations ensued between myself and Shell House. Finally, with the assistance of Jesse Duarte, a date was set for a Mandela dinner. Madiba would fly to address the United Nations in September 2003 and, on his way back to South Africa, he would stop for an evening in Brussels for a dinner.

The dinner was a sophisticated and sparkling affair punctuated with expensive champagne, white-gloved waiters, silver cutlery and canapés. The Chateau de La Hulpe outside Brussels was filled with dignitaries who had flown in from throughout Europe. The most prominent business leaders in Europe lined up with ambassadors to the European Union to have their photographs taken with Mandela.

During his eloquent speech to the gathering, Mandela spoke about his association over decades with the Jewish community, about his Jewish lawyers and about Helen Suzman and how she had campaigned as a lone voice in Parliament for his release. He even spoke about a Jewish lawyer named Lazar Sidelsky, the only man willing to give him law articles in his youth.

The Mandela delegation included many of the leading figures within the ANC at the time and Allan Hirsch, deputy head of the President’s policy unit, recently reminisced to me that that evening was one of the most impressive gatherings he has ever attended.

Sorry, fella, no job here

When Madiba finally found a home and moved into Houghton, he went house to house to introduce himself to his new neighbours. A friend of mine later told me the story that Mandela knocked on his grandfather’s front door to introduce himself. The elderly Jewish man, upon seeing the distinguished black gentleman, but not recognising him, immediately apologised to him for being unable to offer him a job.

Mandela assured him that he had another job waiting and the gentleman need not worry.

Over my six years of running elections with the Independent Electoral Commission, I dealt with Mandela on a number of occasions.

Lying on the lawns of the Union Building in 1994, watching Mandela take the oath of office was a mixture of ecstasy and relief. I had been so sleep deprived during the chaos of our first democratic election that, at one point in time, I fell asleep during the inauguration.

I will, however, never forget the fly-over by the SANDF trailing the new South African flag – for at that moment, for the first time in my life, I felt proud to be a South African.

Howard the tour guide

Howard the tour guide

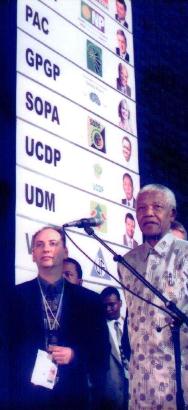

During one visit to the Election Centre in 1999, I escorted Madiba on a guided tour of the Results Centre in Pretoria. Our short stroll turned into an almost hour-long walk as Mandela stopped to greet and talk to almost everyone in the entire hall. Carried on live television, as the two of us meandered around the Pretoria Showgrounds, I can’t help thinking that this did not make for riveting TV viewing for anyone other than my mother.

RIGHT: It made riveting TV-viewing for his mother, says Howard – who ran the 1999 elections

I would occasionally pop into the Union Buildings at the invitation of Presidential Spokesperson Parks Mankhalana, whom I had taken to Israel as part of the SAUJS/ANC Youth League Study Mission in 1992.

Parks was always concerned to know what the Jewish community was thinking of Mandela and his presidency. At a presidential dinner for Jacques Chirac, held in Pretoria in 1998, I remember thinking how strange it was for a dancing Madiba to be swamped and mobbed by the local dignitaries while President Chirac went basically ignored.

Mandela, like no one else, understands the importance of symbol. His number six Springbok rugby jersey at the Rugby World Cup will forever represent a pivotal moment when many white South Africans bought into the unity of a new nation. His philosophy of reconciliation, forgiveness and nation-building can probably best be attributed to the enormous influence of Walter Sisulu on his thinking and life.

Madiba joked about Chaskalson’s wedding gift

Mandela though, mixes ideology with humanity, humility and humour. One can only see these traits emerge in small stories about the man rather than in grand gestures, for it is in these moments that his true humanity shines through. Arriving at Jerome and Jacky Chaskalson’s wedding, in the garden of Arthur and Lorraine Chaskalson, Mandela joked with me that my gift would find far better use with him rather than in the pile of presents lying at the door.

One day in 2001, while driving into the Mandela Foundation in Houghton, my car was blocked by the Mandela cavalcade trying to exit the gate. I reversed out of the yard to let them pass and Mandela wound down his window to thank me for this courtesy.

Humour and humility

As Mandela transitioned from the seat of power, he realised that his legacy could best be preserved by his ability to draw resources and publicity to the areas of his greatest concern: children, education, poverty and AIDS.

On his 90th birthday, how can we truly give thanks to the man who saved our nation, who taught us the meaning of humanity and who proved to us that good will always triumph over evil, no matter what the odds?

I believe the Mandela legacy should live in each of us. We as a Jewish community should dedicate ourselves to expunging racism from ourselves and our land, we should strive for human rights for ourselves and for others, and we should never do anything that does not have morality as its driving force.

On this momentous anniversary let us also pay tribute to the Jewish contemporaries of Madiba, who played their part, big and small, in the struggle. Let us use this moment to give thanks to those of our own, too numerous to mention, who paved the way for our freedom in South Africa today.

- Howard Sackstein is a lawyer, businessman and former anti-apartheid activist with a lengthy record of Jewish communal service. He worked at the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) for six years ending as executive director largely responsible for the 1999 general election. He is also a director of the South African Jewish Report