click to dowload our latest edition

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Published

8 years agoon

By

adminJACK MILNER

Iconic tennis star Billie Jean King once told a bunch of under-12 and under-14 “wannabe” tennis stars that it was important they know their history. “How will you ever know where you are going to if you don’t know where you’re coming from?” she asked them.

Jewish sports history is fascinating because physicality disappeared from the Jewish psyche after the defeat of Judea by the Romans. As Jews moved into the Diaspora and became segregated from others societies, life moved more towards religion.

The focus was on studying and probably led to every Jewish mother wanting her son to become a doctor, lawyer or accountant.

But from the time of Moses through to the likes of Bar Kochba, fighting was part of Jewish life. We fought our way into the Land of Israel and had to fight to defend it. So it comes as no surprise that so many Jews have been prominent boxers. In fact, it was a Jew – Daniel Mendoza – who forever changed the stereotype of Jewish “sissy”.

Daniel Abraham Aaron Mendoza was born on July 5, 1764 in Aldgate, London and died on September 3, 1836.

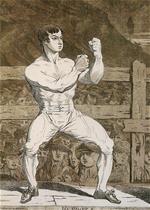

He is regarded as the father of scientific boxing. At a time when the sport of boxing consisted primarily of barehanded slugging, Mendoza introduced the concept of defence. He developed the guard, the straight left, and made use of sidestepping.

This new strategy – the Mendoza School, also referred to as the Jewish School – was criticised in some circles as cowardly. But it permitted Mendoza to fully capitalise on his small stature, speed, and punching power.

This new strategy – the Mendoza School, also referred to as the Jewish School – was criticised in some circles as cowardly. But it permitted Mendoza to fully capitalise on his small stature, speed, and punching power.

His first fight was in 1780 when he was 16. He was working for a tea dealer in Aldgate and the fight was to settle a dispute with a porter over the latter’s remuneration for a consignment of tea. Mendoza stated that the porter, rather than charging his regular fee, “behaved in a manner unfit for a gentleman”, demanding twice the usual price.

After much arguing between the proprietor of the tea dealership and the porter, the porter suggested that they should settle the dispute with fists. Mendoza believing that the porter was bullying his employer accepted the challenge on his employer’s behalf. The fight took place in the street outside the tea dealership in a hastily constructed ring.

The fight lasted some 45 minutes, ending when the porter declared he was unable to continue. This victory brought a small measure of fame to Mendoza as stories of the fight spread through the surrounding neighbourhoods. They portrayed Mendoza as a talented whippersnapper who had not just beaten, but thrashed his larger opponent.

His early boxing career was defined by three wins over his former mentor, Richard Humphries, between 1788 and 1790. The first of these was lost because Humphries’ second (the former champion, Tom Johnson) blocked a blow.

The third bout set history in another way. It was the first time spectators were charged an entry fee to a sporting event. The fights were hyped by a series of combative letters in the press between Humphries and Mendoza.

Mendoza’s memoirs report he got involved in three fights while on his way to watch a boxing match. The reasons were: someone’s cart cut in, he felt a shopkeeper was trying to cheat him, and thirdly, he did not like the way a man was looking at him…

According to the Ring Boxing Record Book, Mendoza was undefeated in 27 straight fights prior to 1788. Bare-knuckle fights ended when an opponent was knocked out or unable to continue or by foul or a draw. Mendoza defeated his first 27 opponents by knockout.

Though he was only five feet seven inches (170 cm) tall and weighed only 73 kg, Mendoza was England’s 16th heavyweight champion from 1792 to 1795, and is the first middleweight to ever win the heavyweight championship of the world.

In 1789 he opened his own boxing academy and published the book The Art of Boxing on modern, scientific-style boxing, from which every subsequent boxer learned.

Mendoza, a descendant of Spanish Marranos who had lived in London for nearly a century, became such a popular figure in England that songs were written about him, and his name appeared in scripts of numerous plays.

His personal appearances would fill theatres, portraits of him and his fights were popular subjects for artists, and commemorative medals were struck in his honour.

Mendoza was one of the inaugural group elected in 1954 to the Boxing Hall of Fame and of the inaugural class of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

Mendoza helped transform the popular English stereotype of a Jew from a weak, defenceless person into someone deserving of respect. He is said to have been the first Jew to talk to King George III.

There has always been a discussion about comedian Peter Sellers having Jewish blood. That is true. He was, in fact, the great-great-grandson of Daniel Mendoza.

nat cheiman

Sep 21, 2016 at 6:34 pm

‘There have been many Jews who have held boxing champion belts.

Slapsy Maxie Baer (heavyweight), Nissim Cohen (Middleweight), Benny Leonard ( lightweight); Barney Ross ( Welterweight); Ted Kid Lewis ; Abe Attel; Maxie Rosenbloom; battling Levinsky;Jack Berg; All World champions. There were more but these are the main ones.’

ASHER

Oct 2, 2016 at 12:20 am

‘On the subject of Jewish boxers – read \”Tunney\” by Jack Cavanaugh – especially the chapter \”The Great Bennah (Benny Leonard) and Barney Lebrowitz (Battling Levinsky)\”‘