Lifestyle

Making the silence of genocide speak

Published

2 years agoon

How do you explore an entire community that was obliterated? How do you capture the individual victims of genocide? How does a landscape absorb history? These are some of the questions that haunt us as Jews. For award-winning artist and photographer Barry Salzman, they are the driving force behind his work.

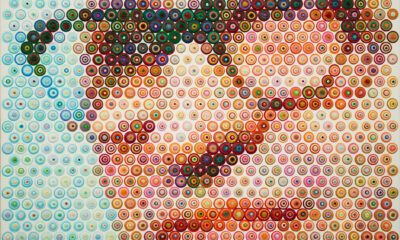

Salzman’s images capture the arc of atrocities across space and time in the 20th century. The result is startling, unsettling, and provoking, forcing the viewer to look at the role they can play in making “never again” a reality.

Salzman was born in Zimbabwe, where he lived until soon after his Barmitzvah. He spent the rest of his childhood in South Africa and emigrated to the United States soon after finishing his studies. Now, he’s back in Cape Town to exhibit at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair (ICTAF), and his work will also make its way to the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre in April. No matter where he has gone, his Jewish identity has motivated him in the stories he wants to tell and the questions he wants to ask.

“Both my father’s parents were born in Zimbabwe,” Salzman says. “My maternal grandparents were from the island of Rhodes, and came there as part of a pre-war emigration wave. My interest in genocide stems strongly from my Jewish heritage and the Holocaust, and my work focuses exhaustively on 20th century genocide, from Namibia, to Poland, Rwanda, Rhodes, and the Ukraine. It’s an ongoing project, and I still hope to explore the Bosnian, Armenian, and Cambodian genocides. The governing principle is a critique of society and our role in stopping the reoccurrence of atrocities. It looks at our unwillingness to confront and engage, and our responsibility to bear witness.”

It’s been almost a decade since he began this work, but it almost never happened.

“I wanted to do a project exploring identity and the cultural heritage that stays with you your whole life, no matter where you go or what you do,” Salzman says. In his own family, he saw that the strong Sephardic culture of Rhodes remained a pivotal feature, while Ashkenazi heritage was less prominent. This led him to start a project interviewing Jewish survivors of Rhodes. At first, he decided there would be no mention of the Holocaust, because he didn’t feel like he had the experience to carry those stories. In addition, many of the people he interviewed had never spoken of their experiences.

“But it was extraordinary. I would ask them their name and where they were born, and that was it – they began to tell their story. Maybe it was because they were at a stage of their lives when they realised they may never have another opportunity,” Salzman says. In that safe space, survivors began to share memories, and Salzman felt obligated to record them and share them with the world. The result was It Never Rained on Rhodes, a short documentary that captures the idealised, longed-for community that once was and can never be replaced.

His ongoing project, How We See the World, explores how the landscape is a witness but also indifferent to genocide. It’s a metaphor for how humanity also witnesses so much and how we try to evade responsibility. “I compare it to watching a scary movie through a gap in our fingers – we know what’s going on, but we put up a filter to prevent the impact.”

These images are purposefully aesthetically pleasing, and Salzman hopes that they go up on walls and evoke important conversations in living rooms and around Shabbat tables. “The minute we restrict these discussions to museums or schools, we become part of the problem,” he says. He understands that people need to compartmentalise in order to function, which is why he thinks art plays such an important role in engaging viewers in a new way.

Salzman’s possibly most startling work is The Day I Became Another Genocide Victim, a series of “portraits” of clothing worn by Rwandan genocide victims on the day they were killed. I was wearing my favourite party dress, I was wearing my favourite shoes, but one got lost, and I was carrying my doggy backpack are just some of the work’s titles. This is also a project that almost never came about.

“It found me,” says Salzman. He was in Rwanda photographing landscapes when news broke of a mass grave discovered near Kigali. “We went to see the excavation, and clothes were just coming out of the ground, piling up. It almost compounded the dehumanising way in which these victims were killed. As each piece was carefully laid out, still damp from the earth, I found myself imagining that person’s story.”

Salzman was so affected that a few days later, he applied for permission to photograph the items. While the people helping him wore gloves, he insisted on gently detangling the clothes from bones, skulls and dirt with his own bare hands.

“I had to handle the garments, separate them, and show that each one belonged to an individual human being. It was the most extraordinary experience. These are definitely portraits of real people, not still-life images. And the thing is, how do you ever stop? There must be millions of garments like this buried around Rwanda.

“A survivor told me that she was lying under a pile of bloody bodies, pretending to be dead and hiding from the killers, when she heard one of them say, ‘I just need one more, then I’ll get to a hundred.’ In tribute to her, and in defiance of the way that perpetrator reduced people to numbers, I decided to stop at a hundred,” says Salzman. “The last image is just a grey square called We Were, because the large majority of victims will never be individually identified, and many of their clothes [and bodies] were hacked to pieces.”

ICTAF is the first time that the project will be exhibited in its entirety. Its display at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre will begin on 7 April 2022, the 28th anniversary of the day that the Rwandan genocide began. The exhibition will most likely be up for a full 100 days, which is as long as the massacre lasted. Salzman’s goal is for this exhibition to be seen by as many people around the world as possible by the 30th anniversary of the genocide in 2024.

He notes that people feel they “know this story” because they have been inundated with Holocaust and genocide history their whole lives. “But actually, we don’t know this story, and we’ll never truly understand the loss and trauma that people endured. The more I learn, the less I know.”

But, by bearing witness now and in future generations, we may just touch the surface and explore what’s underneath.

- The Investec Cape Town Art Fair will take place at the Cape Town International Convention Centre from 18 to 20 February 2022.