Ant Katz

“The perpetuity of online journalism”

Published

9 years agoon

By

adminIn last week’s Mail & Guardian, the acclaimed newspaper’s highly respected ombud, Franz Krüger, wrote his weekly piece on: “The perpetuity of online journalism” which ran under the strapline: “The biggest challenge of an online presence is that material on the web remains there forever”.

How true this is – and, as it turned out, if one looks at the M&G’s Online version of this self-same op-ed, it now contains a footnote which notes that the reader is seeing an “updated version” of the print article: “The name of the reader who shared the name of a government official was removed from the original version of this column, at his request.”

That’s all very well, but, as Krüger’s headline so correctly stated, a Google-search of “The perpetuity of online journalism” resulted in “about 63,500 results” (in 0.52 seconds) – many of which contain the name of the person (whom I shall, here, allow the desired anonymity).

Franz Krüger’s point, published on December 19 2014, is well-founded, therefore, as neither he nor the M&G can deal with the proliferation that online journalism has once it starts spreading.

Beware of social media, too

Krüger’s cautionary note applies as much to the social media space as it does to websites and other digital content. A large proportion of the 63,500 web-places that carried his own piece would have included blogs and all social media platforms monitored by Google Search.

Just days prior to Krüger’s piece being published, on 15 December, the SA Jewish Report published: TUTU VS. REICH MATTER SETTLED WITH AN APOLOGY. By 19 December, the day Krüger’s “The perpetuity of online journalism” was published, the Jewish Report story had already appeared on IOL.co.za – as well as 68,400 other web-spaces!

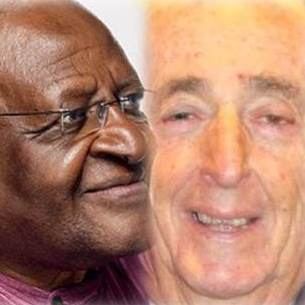

FACE-OFF: Leon Reich and Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The matter pertained to an op-ed piece by right-wing community leader Leon Reich that had been published on September 10 on this website. In Reich’s op-ed, he referred to Archbishop Desmond Tutu in a disparaging manner in response to an August protest march in Cape Town when Tutu urged Israel’s leaders to turn away from policies that humiliate and undermine Palestinians.

Reich’s op-ed was subsequently taken down by the Jewish Report website – but the cat was out of the bag and it was ultimately quoted, in many places in full, on internet pages worldwide. The proliferation of Reich’s article has reached over two million web pages and continues to grow strongly as world Jewish media do not share the “hands-off Tutu” approach when he slates Israel and supports her enemies.

Of course, many of the places that the article appears are pro-Palestinian as well – as “Arch” is a well-known fighter for the cause of the US-based NGO, BDS, and other pro-Palestinian causes – even to the extent of calling for cutting ties with Israel despite PA President Mahmoud Abbas telling the world not to do so.

Tutu, who IOL quoted as being “in a bad state” last week after undergoing a new course of medication for prostate cancer, said: “I accept the apology (from Reich) and consider the matter closed.” Tutu’s lawyer Jonathan Mort confirmed that he had received Reich’s written apology last month and considered the matter closed.

“The perpetuity of online journalism”

Franz Krüger’s piece as it appears on the M&G website:

A reader offended by obscenities in online comments, a man who shared the name of a former government official and a Christian charity running a home for Aids orphans recently asked for material to be removed from Mail & Guardian‘s website.

In various ways, they illustrated the increasingly complex matter of balancing legitimate individual claims of various kinds against freedom of speech on the ever-present and permanently accessible internet.

LEFT: Franz Krüger is adjunct professor and director of the Wits Radio Academy. He is also the ombud for the M&G, a member of the South African Press Appeals Panel and the editor of www.journalism.co.za. He has written two books and is a journalist of some 25 years’ experience, has worked in print and broadcasting in SA, Namibia and the UK. Krüger was part of the first management team of the democratic era at the SABC

The first request was relatively simple and online editors swiftly removed the offending comment from the paper’s Facebook page. It had to do with a report on a Botswana decision to impose a visa requirement on leaders of the Economic Freedom Fighters.

The rules for online comments are clear: the newspaper encourages civil discussion, and racist and defamatory material will be removed. Although the odd swear word may be tolerated, “gratuitous profanity won’t do”, the rules say.

The others were more difficult. In one case, a reader wrote to complain about a 2007 report about the former head of the Mining Qualifications Authority, with whom he shares a name. He argued that he had been prejudiced by the reporting of mismanagement claims against his namesake, apparently also a relative.

Even before considering the request to have the article removed, I had to point out that the coincidence of a common name is not grounds for complaint. In case the issue comes up, it should be relatively easy to point out that the reference is to somebody else. There are probably many cases where people share names with others in the news.

Then there was the case of Bulembu Ministries, which complained about a report on the home for Aids orphans it runs on the site of a disused asbestos mine in Swaziland.

The report raised questions about the health risks arising out of the remaining asbestos fibre in the dumps. The ministry argued levels of fibre were very low, far beneath legal limits, and that the report overstated the risks. Bulembu said it unfairly harmed the reputation of a worthwhile initiative, and might harm its ability to raise funds.

The complaint led to an extensive correspondence as I tried to clarify some aspects. In the end, I believe there are a few aspects where the ministry’s perspective should be added to clarify its position.

But I did not think the report should be removed. There was public interest in the story, and any weaknesses were not fundamental. Instead, some additional points and clarifications have been posted with the online article.

As I pointed out to the ministry, removing a report from the website is an extreme step, and is only appropriate under unusual circumstances.

There are several reasons online publishers are hesitant to take down material. For one thing, it is generally an exercise in futility as it is almost impossible to remove items completely. They live on in search histories and caches, and may have been reproduced elsewhere. Material on the web is forever.

There is also an issue of principle, because a published report becomes part of the public record that should not be lightly tampered with.

Removing an article is a bit like destroying books in a library. It is better to make sure that errors are corrected, so that when the report is found, any corrections of fact or perspective are also immediately available to the reader.

Of course, there are exceptions. There may be cases where the harm caused is so grave that only the complete removal of an article will serve. Even then, though, there should at least be an indication that this has been done.

The real significance of the permanence of online journalism lies elsewhere, I think. It can be very unfair to leave reports open-ended. A report that charges have been laid leaves a particular impression: no smoke without fire, people are likely to say.

If a subsequent acquittal is not also reported, that suspicion can remain in place. And yet journalism online is full of stories that begin but don’t end.

Setting out to track stories to their logical conclusion is easy when it comes to high-profile cases such as that of Shrien Dewani and, in any event, one can rely on the fact that the pack will cover it thoroughly. But there are many others that are harder to track.

If they are lucky, further developments take place on quiet news days, and they can be accommodated by newsrooms that are under increasing pressure.

It’s not really good enough, and yet practical considerations make it all but impossible always to cover stories to completion.

The Mail & Guardian‘s ombud provides an independent view of the paper’s journalism. If you have any complaints you would like addressed, email ombud@mg.co.za

- The name of the reader who shared the name of a government official was removed from the original version of this column, at his request.