Featured Item

“Crazy” innovator helps Wits make quantum leap into the future

Published

2 years agoon

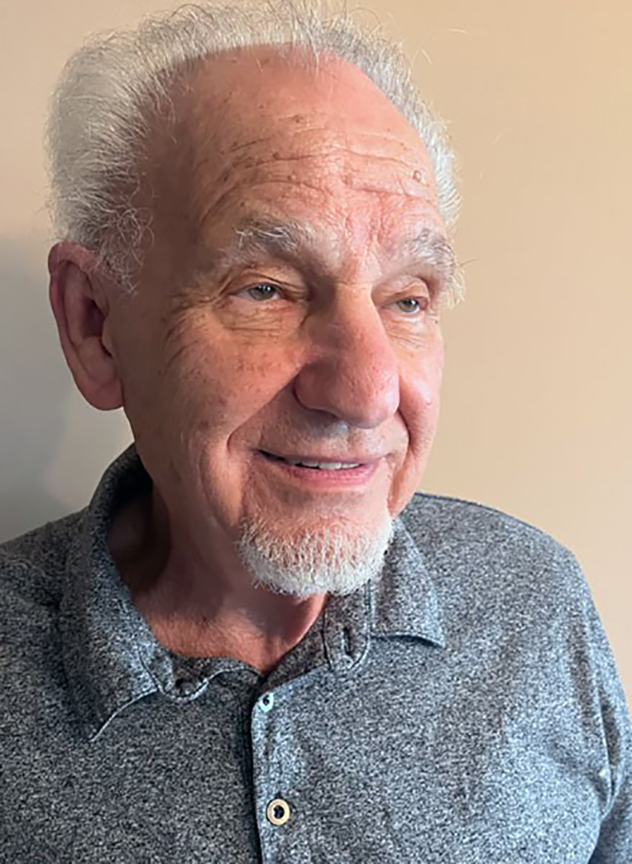

“People think innovators must be geniuses – super-intelligent people with phenomenal memories. Absolute nonsense,” said South African-born and University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) educated innovator and entrepreneur, Dr David Fine, last Thursday, 31 March.

“Other people believe that innovators are childhood prodigies. Again, total nonsense. Take me as an example. I failed first grade, and I did very poorly at school. Yet, later on, I learned how to innovate.”

Fine may well not have been a top scholar, but he looks back at his years at Wits with gratitude. So much so, he recently donated $3-million (R43.7 million) to his alma mater.

Fine was heeding Wits’ call to help establish an ecosystem for researcher-led innovation at the university. The idea of assisting in solving some of Africa’s biggest challenges and advancing the public good appealed to him.

The money will be used to establish the Angela and David Fine Chair in Innovation. Speaking at a webinar about “innovators as problem solvers and setting the direction for Wits in its second century”, Fine said he hoped the chair would put Wits at the forefront of innovation in the global South.

Wits vice-chancellor and principal, Professor Zeblon Vilakazi, said in the webinar, “Thanks to David and Angela Fine, this university has taken a quantum leap into the future with the establishment of the chair.

“It’s a very generous donation into an endowment fund to support innovation at Wits and to create a long-lasting legacy of upliftment, forward-thinking, and relevance.”

This year, as Wits is celebrating its centenary, it has identified innovation as one of its major strategic thrusts.

Fine, now retired, is passionate about inspiring a new generation of innovative problem solvers. He graduated from Wits with an honour’s degree in chemistry in 1964. Numerous members of his family, including Rivonia trialist Arthur Goldreich, were anti-apartheid activists. Not only did they become enemies of the state for their opposition to the system, but Fine’s sister, Sunday Times reporter Hazel Fine, was also a marked person.

Around 1970, Fine fled the country. He got his PhD from Leeds University in the United Kingdom before leaving for the United States to run the Combustion Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In response to the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie in Scotland, Fine developed the first airport sniffers that could detect traces of plastic explosive residue in passenger luggage.

After working at Thermo Electron (now Thermo Fisher) for 28 years, he formed two companies of his own – CyTerra in 2000 and Vero-BioTech in 2006.

In the field of analytical chemistry, Fine developed a way to detect traces of chronic nitrosamine, chemical compounds associated with numerous cancer sites. He also developed a handheld detector for finding buried landmines.

Fine said there were many misconceptions about innovators, including that they needed to be highly knowledgeable about their subject.

“That couldn’t be more incorrect,” he said. “The more the person knows about their narrow little subject, the more brainwashed they are. They know so much, they’ve got nowhere to turn. They can’t innovate.”

We’re all born with the innate ability to innovate, he said. “Five-year-old kids playing in a sandbox are innovating and playing imaginary games, with toys, locks, and paints. Every one of us innovates every day in our daily lives. We cook using new recipes, we select what clothes to wear, we decorate our homes.”

According to Fine, when innovators look at a new topic, they should read about it for a couple of days just to understand the problem. “Then stop. Go and think about how to solve the problem. You’re not an expert, but you can solve it. You may find half a dozen possible solutions.”

Fine cited Buddhist monk Shunryū Suzuki, who said, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s, there are few.”

Once you have found solutions, you become the expert. “In innovating, one of the key things you have to do is grasp the key fact of a problem. Focus on it, and solve it.”

To train himself to do this, Fine would read a paper or watch a movie and then summarise it in just a couple of paragraphs.

He once asked one of his brightest engineers to summarise two pages of an interesting paper he had seen. “His summary of the two pages was ten pages,” recalled Fine. “He couldn’t prioritise. Everything they did, he thought, ‘Well, maybe they didn’t consider this and that’. He’s very good at writing papers, but as an innovator, he couldn’t innovate.”

This made Fine realise that there are two kinds of scientists, those who publish and extend knowledge, and those who innovate. He said the latter scientists are scarce, and South Africa needs more of them.

Emphasising that innovators need to be correct, Fine said he verified the results of his experiments. “I would check the recalibration, get chemicals from two supply houses, check every equation and formula. I would repeat the entire experiment with different apparatus if I could. If it was important enough, I did it myself over a long weekend.”

He said that when people question your innovations, you should be able to sit back knowing “you’re right, and they’re wrong”.

“When you come along as an innovator and you propose something which is counter to [scientific belief], or you have actually got something working which is counter to that, or you’ve got data which is counter to that, people get instinctively negative,” Fine said.

In 1975, Fine was notified that his contract with the US National Institutes of Health was being cancelled. He was told he was “incompetent and stupid” because one of the reagents he added to a sample wasn’t approved. When it was soon realised that he had found the solution, he got his contract back.

“I’ve been called incompetent, stupid, crazy, an ignoramus, charlatan, trickster, a son of a bitch. That’s happened to me not once, but more than a dozen times. It happens when you disrupt the very powerful egos of people who have made it to the top in their field.”