Lifestyle

Charcoal breathes fire into African artist’s Jewish works

Published

3 years agoon

By

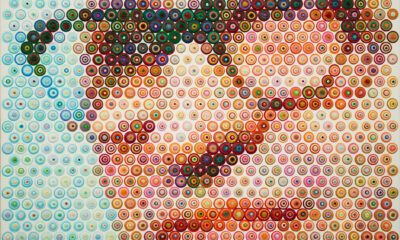

Mirah LangerA man wrapped in tefillin, head bowed in prayer against a background abstracted with an intensity of brush strokes; Haredi scholars striding like warriors; soldiers’ heads pressed against Kotel stone; a young girl enfolded in a windswept Israeli flag; an elderly scholar illuminated by light: These are just some of the iconic scenes of Jewish and Israeli life rendered in charcoal by a remarkable new South African artist, Treatwell Mnisi.

“I am myself, in my heart, an Israelite of some sort,” is how Mnisi, born in rural Mpumalanga, describes the unique intersection of his African identity and the Judaic and Israeli subject matter of his work.

“The Jewish art that I do; it’s already a living thing. The Jewish people live it; they practice it. I’m merely a vessel to bring that into fine art. I am simply somebody who is showing them the greatness that they already have.”

Mnisi’s unique artistic style was discovered by members of the Jewish community, who have since formed a team to help him showcase his work. Most recently, Saul Jassinowsky, Gila Zulberg, Gila Abramson, and Daniella Ash helped host his first solo exhibition.

Zulberg, a rebbetzin and an artist herself, and Jassinowsky, a businessman, were the first to hear about his art. “It’s such a different kind of stroke, very expressive. I found it to be a deep and proper understanding of movement,” says Jassinowsky about what moved him in Mnisi’s style.

Beyond his talent, Jassinowsky was impressed at how Mnisi engaged in the world. He recalls a fundraiser where many upcoming artists had their pieces on show. “None of their pieces sold for values, except Treatwell’s, which sold for five times its value. When his friends’ pieces weren’t selling, he picked the pieces off the wall and walked around, encouraging the crowd. He is this small guy, but he put in the effort. I just thought: he’s a mensch.”

Jassinowsky decided he wanted to try and help Mnisi. He and Zulberg then thought of commissioning Mnisi to make works related to Judaica and Israel. “I always have to go overseas or look in Israel to find something Jewish to put on my walls. You can’t really find anything here,” says Zulberg.

Ash, a South African interior decorator living in Israel then brought Abramson into the fold. Although a lawyer in practice, Abramson has been extensively involved in curating African art. They planned to host a small gathering at one of their homes with maybe 20 pieces on this theme.

“I sent him three or four ideas, but he just didn’t stop,” recalls Zulberg. “He just painted and painted and painted and painted. We ended up with 100 pieces. The night before the exhibition, an Uber arrived at my house with an extra 28 pieces.

“The charcoal was still wet,” recalls Jassinowsky.

The exhibition, held at Under the Trees, a restaurant in Johannesburg, left people mesmerised. “There’s been an outpouring of awe at how he has captured Jewish experience,” says Zulberg.

What was incredible was the thought and emotion behind the work, says Abramson. Mnisi relentlessly researched and questioned in order to understand the full meaning behind the imagery he was capturing. “He said when it’s right; it’s respectful. He has such a huge amount of respect for the religion.”

Mnisi has the highest regard for his connection with these community members, and a deep sense of gratitude. “My favourite person in the world is Grandpa Mandela. According to him, we are a nation, and we must build a system in which all people are able to coexist,” he says. “Being with Saul, Gila, Gila, and Dani is a beautiful thing. It was meant to be. Their coming into my life and my coming into theirs, it’s two sides coming together as one, doing the very thing that we’re supposed to do as blacks and whites: come together for a specific purpose and find common ground in what we do.”

Mnisi says his earliest memory is of drawing at the age of three. After matric, he followed his passion and started studying at the Tshwane University of Technology in fine and applied arts. However, as a result of difficult circumstances, he couldn’t continue, and instead entered “the nine-to-five hard labour, minimum-wage industry. I was mixing concrete, cement, building RDP houses, working as a gardener. My last job was at a car wash.”

Then COVID-19 hit. “Although it’s a pandemic and not something good for us as human beings, for me, it was a blessing,” Mnisi says. Working as a night security guard at a crèche during lockdown, he had “time to think about my life, my dreams, and whatever it is I want to do”.

He also reunited with renowned artist Azael Langa, whom he had previously known at university. “He started to tell me about all the endless possibilities that we can have as artists if we put our minds and hearts into it. He gave me a piece of charcoal, but I told him I don’t do charcoal, I’m a pencil guy, I use oil paints for superrealism.”

Langa said, “Do the opposite of what you normally do.”

In hindsight, Mnisi realises that it was a process of coming full circle. “As a child growing up on my mother’s side in the village, after they cooked, I would go to the ashes to find charcoal to draw with. It was my first love.”

He returned to the visceral experience of painting with his thumbs, and started creating impressionistic works radically different to what he had done before. Since then, he also incorporates tools like rubber brushes in his process.

He recalls his first encounter with Jewish life as a small boy in Middelburg. “I remember as a kid going into the city, and I saw these men dressed up in black suits, coats, and hats. So I asked my grandfather, ‘Who are those people?’ And my grandfather said, ‘Those are the Jews.’” I said to him, ‘The Jews from the Bible?’ and he said, ‘Yes, those are the descendants of the Jews from the Bible.’ That day, I vowed that I would become friends with a Jewish boy because I was still a little boy, but I never did. And now that I’m a grown man, guess what? I meet two brothers [Jassinowsky and his brother] and they have become my friends.”

When Jassinowsky sent Mnisi Psalm 121 as inspiration for the exhibition, Mnisi not only recognised it as “scripture I used to read to my mother”, but took it as a deeper “subconscious, spiritual” sign. It was telling me “’to lift up my eyes”. I thought back to the conversation with my grandfather telling me, ‘Those are Jews.’ Those Jews dressed in monochrome, and my art is monochrome. I could see the art before I even started.”

He dreams some day of “mixing this project with my own African culture. Imagine putting a Jewish guy next to a Swazi guy: one dressed in his Jewish regalia, the other in his Swazi wear. They are sitting together. That would be a beautiful piece.”

It’s an image that evokes Jassinowsky’s reflections about the deeper meaning behind their cross-cultural interaction: “A founding tenant of Judaism is to look outwards and reach outwards. It’s a reminder that we can’t exist in isolation. We have to engage. We have to reach out and people on the outside need to reach in.”

Treatwell

Jun 10, 2021 at 12:21 pm

This is a wonderful article;it lays emphasis on the the power of love for self and also others. Acknowledging our differences and embracing our similarities. I thank Ms Langer who captured the essence of a partnership between people who share a common goal and vision 🙏🏽